Self-driving vehicles are fast approaching commercialisation in markets across the world. By 2035, 40% of new cars in the UK could have self-driving capabilities. Grocery deliveries and passenger services look likely to be operating in self-driving vehicles within a similar timeframe. This will be the future of road travel, but we are at the beginning of this journey, and human drivers will share the roads with self-driving vehicles for many years to come. It is therefore vital for us to manage the changes that connected and self-driving technologies will bring by introducing the right rules, training and support at the right time.

The potential benefits of connected and self-driving technologies are considerable: from better integrating rural communities and reducing isolation for people with disabilities or older people, to helping deliver essential goods and improving access to education, work and leisure.

Intelligent vehicles will communicate not just with each other, but also with road infrastructure such as traffic lights, helping minimise congestion.

These technologies could also make our roads safer, reducing the number of collisions involving human error – which is currently a factor in over 80% of collisions that result in personal injury. Self-driving vehicles won’t get tired or distracted. They won’t worry about the children in the back seat, stress about their next meeting or be anxious to get home for dinner. They are likely to react more quickly than a human, remaining consistently able to assess how to drive safely in a fraction of a second.

The UK government Report Connected and Automated Mobility 2025

The UK government Report titled Connected and Automated Mobility 2025: realising the benefits of self-driving vehicles, confirms that the government will consult further on retaining and sharing data with insurers for claims investigations and work with the Motor Insurers’ Bureau on a solution for uninsured self-driving.

The government will engage more widely to understand how product liability law might need to be.

This report is good news. It demonstrates that the UK government has reached two key conclusions.

- First, the Law Commission’s guidance on how to build a new, safety-focused, legal framework for autonomous vehicles should be adopted.

- Second, handled effectively, the introduction of autonomous vehicles onto Britain’s roads by 2025 would be a major technological win for the country.

The successful introduction of autonomous vehicles will bring technological innovations and environmental benefits. Reading the huge detail in this report of the various work streams and action points, it’s clear the government’s goal is for the UK to be at the forefront of this work globally.

However, that timescales detailed in the report are ‘just about realistic’ and that the legislation needed to put autonomous vehicles on the UK’s roads will be ‘heavy’.

It’s going to be a heavy piece of legislation. The government is aiming to implement all of this in full during 2024–25, although we could see automated lane-keeping systems (ALKS) being authorised for motorway use within the next year. We also anticipate significant consultation about the necessary secondary legislation.

New ways of making vehicles safe and testing their safety will ensure the benefits of self-driving technologies become a reality, which is a major focus for this Report.

This need to embed safety is, in itself, driving innovation:

- scenario generation techniques have been specifically developed to help us understand how a self-driving vehicle will behave in millions of situations;

- new sensor technologies, data processing and computational approaches mean vehicles will be capable of perceiving their environments in ways that human drivers will never be able to;

- emerging thinking is happening within the field of AI to enable those self-driving systems that use machine learning to explain their driving behaviour.

The UK market of Self-driving technologies

This new framework will enable innovation whilst also ensuring safety. In addition to the substantial gains in getting from A to B safely, these technologies could deliver huge economic benefits, attracting international investment and reinforcing the UK’s place as a global science superpower.

The UK market alone could be worth as much as £42 billion by 2035, creating as many as 38,000 jobs in the sector. The UK is in an excellent position to secure the benefits of these new technologies, and they can be part of our approach to Build Back Better from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The UK is home to some of the most exciting self-driving mobility companies in the world, who are safely and responsibly setting the standard for global innovation in this space. The UK’s Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles has helped secure over £400 million in joint industry-government funding to date, supporting over 90 projects involving 200 organisations. Last year, government held a call for evidence about the future of the UK Connected and Automated Mobility sector. This has informed our thinking about government’s priorities, and this document contains the government’s response.

Connected and automated mobility (CAM) is no longer a tantalising prospect from science fiction

These technologies could play an important role in how government improves and levels up access to transport across the nation, helping us to build back better and make everyday journeys greener, safer, easier, and more reliable. In the coming years, connected and self-driving vehicle technologies could also bring vast economic benefits to the UK, creating an industry worth billions of pounds and generating thousands of well-paid, skilled jobs across the country.

Government established the Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV) in 2015 to bring together CAM technology developers, vehicle manufacturers and suppliers, academia, insurers, local and regional government, and transport bodies, among many others, to test and develop policy and to build UK capabilities and supply chains.

Through this collaboration, the UK is moving towards a new era of mobility that safely embraces innovation and technology. Reflecting this, the UK is noted as a top 10 market in KPMG’s Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index 2020, leading particularly on policy, legislation, and cyber security.

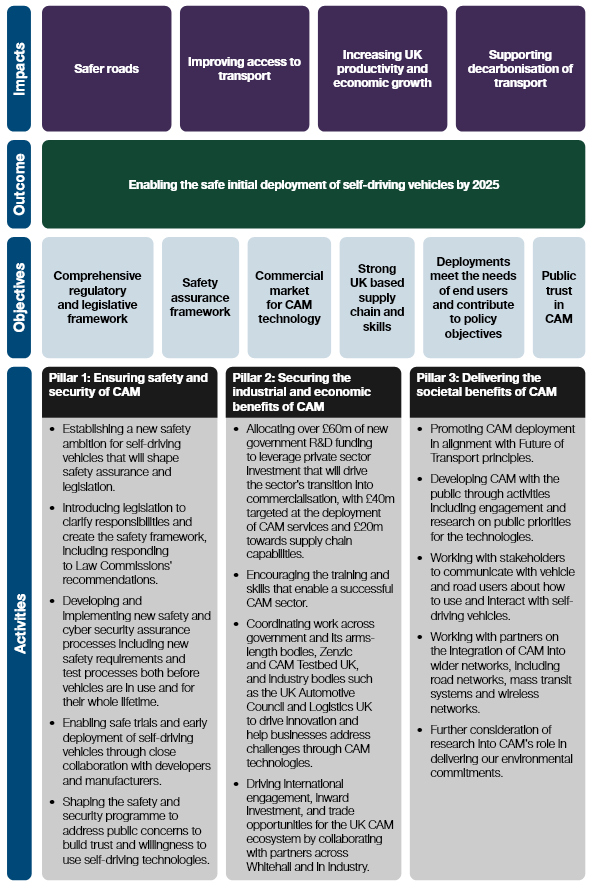

To maximise these benefits, government is committed to working with industry, local government, safety organisations and others as we move towards the safe roll out of these technologies.

Government’s role going forward is to help realise the transport, economic and wider societal benefits that CAM could unlock.

This work sits within the wider context of emerging transport technologies and business models and the Future of Transport programme was created to respond to these radical changes. The programme aims to stimulate innovation, prepare the UK for new technologies, support the transition to zero emission, and create a world-leading future transport system that is safe, secure, and accessible to all.

Government has already set out nine principles that help define our vision for future transport and guide how we can harness the opportunities and mitigate the unintended consequences of profound changes in the way we travel.

Nine key principles from the Future of Mobility

In facilitating innovation in urban mobility for freight, passengers and services, the Government’s approach will be underpinned as far as possible by the following Principles:

- New modes of transport and new mobility services must be safe and secure by design.

- The benefits of innovation in mobility must be available to all parts of the UK and all segments of society.

- Walking, cycling and active travel must remain the best options for short urban journeys.

- Mass transit must remain fundamental to an efficient transport system.

- New mobility services must lead the transition to zero emissions.

- Mobility innovation must help to reduce congestion through more efficient use of limited road space, for example through sharing rides, increasing occupancy or consolidating freight.

- The marketplace for mobility must be open to stimulate innovation and give the best deal to consumers.

- New mobility services must be designed to operate as part of an integrated transport system combining public, private and multiple modes for transport users.

- Data from new mobility services must be shared where appropriate to improve choice and the operation of the transport system.

By 2025, the UK will begin to see deployments of self-driving vehicles, improving ways in which people and goods are moved around the nation and creating an early commercial market for the technologies.

This market will be enabled by a comprehensive regulatory, legislative and safety framework, served by a strong British supply chain and skills base, and used confidently by businesses and the public alike.

Why is Connected and automated mobility Important?

Key opportunities and challenges facing the UK CAM sector, and associatedgovernment actions.

Global market context and the UK CAM sector

The global race to develop and deploy CAM technologies poses significant challenges, and the complexities are not limited to the development of technologies. Public trust, regulatory challenges, and how services are integrated into existing and future transport networks have all raised questions for companies and governments looking to bring self-driving vehicles to market. This has required industry and government in recent years to develop technology, policy, and regulation in lockstep, encouraging open analysis of the barriers facing the introduction of self-driving vehicles and reflected in Zenzic’s ‘UK CAM Roadmap to 2030’ (2019).

The UK CAM sector is now gearing itself up for initial commercialisation, reflecting impressive advances of the technology and service capabilities in recent years.

British CAM companies – many with support from government – have grown to become competitive on the global stage, establishing the UK as a leading destination for developing and deploying the technologies.

Data compiled from publicly available sources shows that, of the ~200 companies who have received government grant funding to date, 35 have secured additional private investment totalling £790 million.

The true level of investment across the sector is likely to be much higher, as this does not include investment in companies who have not received government funding, nor the deals that have not been made public.

Connected and self-driving vehicles could deliver huge economic benefits for the UK, attracting international investment and enhancing the UK’s standing as a global science superpower.

The market in the UK alone could be worth as much as £42 billion by 2035, capturing around 6% of the £650 billion global market, and creating up to 38,000 new jobs4 in the sector.

Respondents to the government’s 2021 call for evidence into the ‘Future of connected and automated mobility in the UK’ stated that the emerging CAM opportunity would not only contribute to future-proofing the UK’s automotive, logistics and mobility sectors, but would also open new markets for other homegrown emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, cyber security, Mobility as a Service (MaaS) and innovative insurance products. These outcomes could support wider government Levelling Up, Net Zero and Global Britain priorities set out in government’s 2021 publication, ‘Build Back Better: our plan for growth’.

A Transport Revolution

Across a range of transport modes, networks and infrastructures, technology is revolutionising how people and goods move around the country.

CAM technologies are at the heart of this, with potential to make journeys and logistics safer, fairer, cleaner, and more efficient:

- Self-driving technologies in zero-emission cars, buses and delivery vehicles could smooth traffic flow and reduce emissions per mile, improving air quality and helping the UK to build back greener to meet its net zero carbon commitments.

- Research has shown that connected services, with traffic lights and vehicles speaking to each other, could help keep traffic flowing, improve safety, ease congestion, and reduce emissions.

- CAM technologies could increase UK productivity by allowing drivers to benefit from optimised route planning and improved traffic flow and by giving them more productive time in their vehicles

- CAM services could improve access to transport for people with mobility issues – those who are losing access to independent mobility as they age and those who have never had access to independent mobility.

- CAM could reduce the cost and improve the reliability of transport services, helping to level-up access to transport in rural and historically disconnected areas.

- Crucially, even at relatively low levels of automation, the technologies could reduce road collisions. At higher levels, it could significantly improve safety on our roads by markedly reducing human error. These opportunities – and how government intends to take advantage of them – are explored further in Chapter 2 of the document.

Successful design and delivery of these vehicles and services will be contingent on effective public engagement, giving confidence the technologies can safely meet people’s transport needs.

The public will need to be able to access the right training, accurate information and supporting products (e.g. insurance) to enable safe use.

CAM technologies will need good digital and data infrastructure for elements of their functionality and the regulatory framework. For example: routing and efficiency services will require connectivity, while the core functions of self-driving systems are expected to function safely without it; data retention will be essential to ensure proper management of incidents involving self-driving vehicles. 4G coverage across major roads in the UK is currently at 66%, with urban coverage at 84% and rural coverage at 57%.

We must also consider how CAM technologies may shape the jobs and skills of the future, ensuring that the technologies benefit society by solving labour challenges, rather than adding to them.

4G coverage across major roads in the UK is currently at 66%, with urban coverage at 84% and rural coverage at 57%

The HGV driver shortage, for example, has brought the skills agenda in the sector into sharp focus, and transport and logistics businesses have noted challenges around the wider skills supply pipeline and staff retention. The government also recognises these challenges and has published the ‘Transport labour market and skills: call for views and ideas’. We are also establishing an industry-led Transport Employment and Skills Taskforce (TEST) to advise on addressing these challenges.

CAM offers one solution – although by no means a panacea – to improve the resilience of the supply chain and the reliability and cost efficiency of the freight and logistics sector, with potential to translate these benefits to adjacent sectors

CAM technologies are also expected to create tens of thousands of good employment opportunities across all skill levels to attract and grow talent.

Government and industry must work together to consider what is necessary to prepare the workforce for increasingly digitised and automated industries.

Self-driving vehicles are a key element of wider CAM technologies

The existing safety framework for roads and road vehicles is extensive – from vehicle standards and driver licensing, to rules of the road and motoring offences; but it has been developed with the human driver at its heart. New and innovative self-driving technologies are pushing the boundaries of existing legislation and safety assurance processes.

Government is therefore undertaking a comprehensive programme of research into the safety of self-driving vehicles and is introducing legislation to create a new safety framework which will enable a new era of safe self-driving road vehicles.

This is facilitated by the UK’s departure from the European Union, which provides us with the platform to capitalise on our regulatory freedoms and make decisions that are right for Great Britain.

The new safety framework will deliver transformational change to existing safety assurance provisions. The framework must allow for the continued innovation that we expect to see as self-driving vehicle technologies develop. We anticipate two broad development routes: vehicles that can undertake part of a journey (requiring a driver some of the time) and are likely to look much like conventional vehicles; and vehicles that can undertake an entire journey (so do not require a driver), which may look novel in design and are likely to be offered as a service.

But these routes may change, so the safety framework must allow for this, as it must also permit for different technical solutions to ensure safe deployment.

This chapter sets out the government’s intended structure for the new framework and the work that is being done to implement it through legislative and safety assurance processes. Primary legislation will be introduced with the intention of setting out the broad structure of the framework, with further detail to be developed and set out in secondary legislation. Both the research needed to support this development and implementation of the framework will continue to be undertaken through government’s CAVPASS programme.

Road safety and technology

While we have some of the safest roads in the world, even in 2020 – when travel was severely disrupted – more than 1,460 people were killed on our roads. This is equivalent to over four people a day, 28 people a week or 122 people a month losing their lives. These figures were higher in 2019, when there were 1,752 road traffic fatalities. This, and the 22,000 people who are seriously injured every year, is unacceptable.

Driver assistance technologies in vehicles are already improving safety on our roads: EuroNCAP and ANCAP assessed that vehicles fitted with low-speed advanced emergency braking (AEB) had a 38% reduction in real-world rear-end crashes compared to a sample of equivalent vehicles with no AEB.

Because human error is a significant factor in many road collisions, self-driving technologies have the potential to further improve safety.

The Institute for Engineering and Technology (IET) claim that for every 10,000 errors made by drivers, a self-driving vehicle will commit just one. This is supported by evidence showing that in 2020, 88% of all recorded collisions on roads in Great Britain involved human error as a contributory factor.

Vehicle technology has already delivered significant advances in road safety and is expected to continue to do so with the right legislative and safety frameworks in place.

Technology is not infallible, and new technologies bring new risks and challenges which must be managed and met. Road safety is also not the result of vehicle technology alone, and can only be achieved by addressing and aligning the many factors that contribute towards it – adopting a ‘safe system’ approach.

Responsible innovation in self-driving vehicles – Centre for Data Ethics & Innovation

Building on the Law Commissions’ review, government commissioned a report by the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) to propose how responsible innovation can be embedded in the future regulatory framework. The CDEI’s report “Responsible Innovation for Self-Driving Vehicles” is published alongside this document.

Their recommendations cover the breadth of the regulatory framework proposed by the Law Commissions, highlighting tangible points at which government can assure the safe and ethical behaviour of self-driving vehicles, leading to fair and equitable outcomes. For example, they have made recommendations on governance and the handling of personal data by self-driving vehicles, the importance of understanding why a vehicle behaved as it did, and the centrality of public trust.

The deliberative research explored the factors that influenced perceptions of safety and the minimum safety requirements that would be required for participants to consider self-driving vehicles as ‘safe enough’.

There were two commonly identified core factors:

- Evidence of safety: Examples that were given during the research included testing and expert testimony.

- Regulation and oversight: Examples that were given during the research included updating The Highway Code and driving tests.

These findings provide support for the safety assurance and legislative reforms that form the basis of government’s new intended safety framework. The research also identified potential levers for accurately understanding perceptions of safety.

Public attitudes to self-driving safety

Advancing Safely to Full Vehicle Automation

In June 2021, government funded four projects, bringing together more than 20 organisations from across industry and academia, to support the development of safety assurance processes through practical application; advancing our understanding of the safe and secure removal of the safety driver from self-driving vehicles.

Sharing £2.3m in government R&D funding, the four projects were

Assured Zero Occupancy with Remote Assistance (AZORA)

Led by Oxbotica, the project focused on the required physical systems and software behaviours to enable the self-driving vehicle to safely respond to adverse situations, including systems failures and unexpected behaviours from other drivers. The project safely demonstrated minimal risk manoeuvres (bringing the vehicle to a safe stop in a safe location) in test conditions with and without a safety driver

in the vehicle, laying the groundwork for the deployment of novel vehicles with no traditional driving controls.

Safe Pathway to Autonomous Control Externally Supervised (SPACES)

Led by Aurrigo, the project was dedicated to the safe operation of low speed automated driving systems using remote monitoring without an onboard safety supervisor. The project assessed the additional safety requirements that arise because of remote supervision, both in terms of implementation and engineering processes, and examined communication requirements that would ensure resilience from signal interference and cyber-attacks.

Safely Advancing Vehicle Automation On Roads (SAVOR)

Led by Conigital, the project focussed on three elements: the feasibility of remote monitoring and teleoperation, including how to ensure the minimum communications requirements for safe operation; developing safety critical “fail-safe” minimal risk manoeuvre systems; and a human factors study that was undertaken in a controlled simulation environment to explore the usability and safety of the systems.

Ensuring cybersecure deployments of driverless teleoperated vehicles (ENCODE)

Led by StreetDrone, the project developed a “multi-driver” system (in-vehicle and remote operator, and self-driving system) and the required safety and cyber security features to ensure safe operation in all modes. To demonstrate the project’s objectives, two “multi-driver” vehicles were operated simultaneously on public roads in London and Oxford.

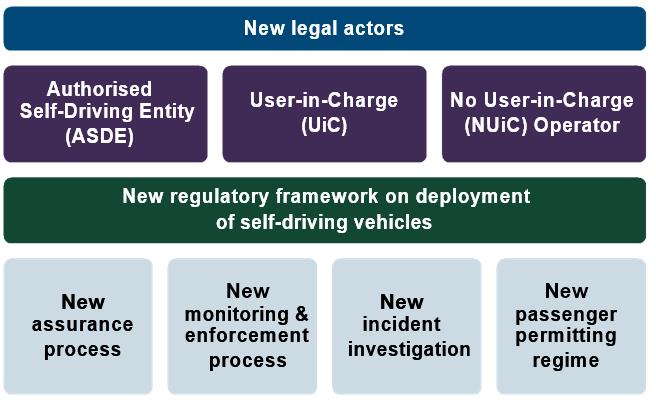

Authorisation to self-drive

Authorisation will assess, among other things, whether a self-driving vehicle can safely and legally drive itself in at least some circumstances or situations. This will build on existing work to develop a ‘monitoring test’19 which seeks to determine whether a vehicle can safely and legally drive itself without the need for monitoring by an individual.

The monitoring test sets out 5 criteria. A vehicle must:

- Comply with relevant road traffic rules

- Avoid collisions which a competent and careful driver could avoid

- Treat other road users with reasonable consideration

- Avoid putting itself in a position where it would be the cause of a collision

- Recognise when it is operating outside of its operational design domain

Authorisation will also consider whether a suitable ASDE can vouch for the safety and lawfulness of the vehicle. An ASDE is the organisation that will be held responsible for a vehicle when it is driving itself. An ASDE will need to be registered, considering whether they are suitable to take on responsibility for a vehicle, such as having sufficient financial standing and good repute.

Data obtained through in-use regulation will contribute to assessment of the aggregate safety of self-driving, and comparisons with the safety of human driving.

Government will publish a regular report detailing its analysis of self-driving compared to human driving. Over time this will help to establish the real-world effect of these new technologies. Appropriate comparisons will depend on the operational use cases for the vehicles with self-driving features, and comparative data is unlikely to be available for every circumstance.

Two categories of self-driving features

We anticipate that there will be two broad categories of self-driving features. The first category includes features that can only drive the vehicle for part of a journey: vehicles with these features require a human driver in the driving seat to take control for the rest of the journey.

For example, the vehicle may be able to drive itself on major roads and in limited weather conditions: if the vehicle is going to turn onto a minor road, or the weather deteriorates, it will issue a transition demand so that the human driver can take over.

In such a vehicle, government intends for the human driver to become User-in-Charge (UiC) when the vehicle is driving itself and therefore no longer responsible for the behaviour of the vehicle.

They will remain responsible for other legal requirements however, such as vehicle insurance, loading and roadworthiness. It is our intention that responsibility for the vehicle’s behaviour will pass to its ASDE.

Key elements of the proposed primary legislation

Government’s intention is to develop secondary legislation that will establish the detailed process by which an ASDE obtains authorisation for their vehicle(s) and the process by which a NUiC operator receives a licence. This will include the requisite fees, evidence required, and appeals process. We also expect to publish further guidance on what constitutes a sufficient safety case by ASDE and NUiC operators, leaning on the CDEI’s recommendations.

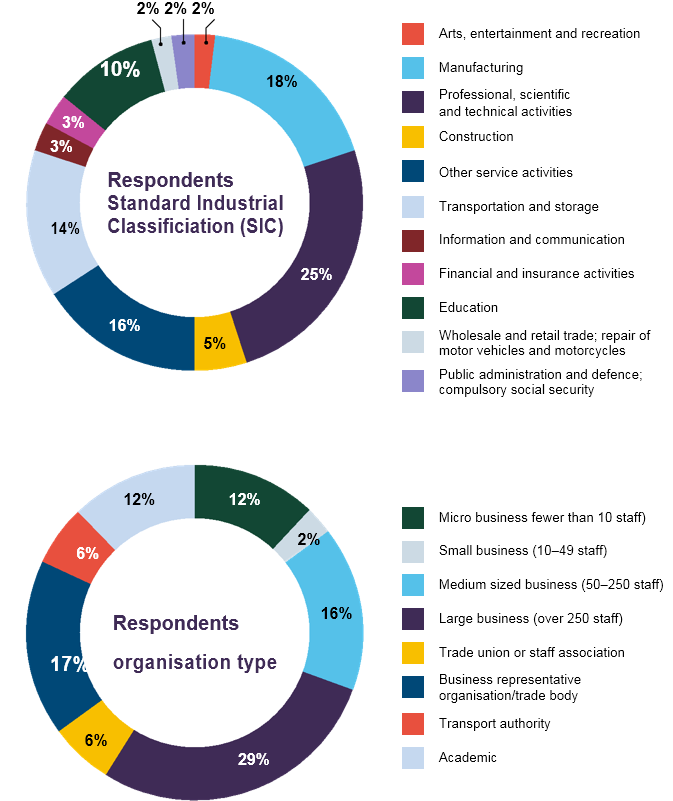

Graphical breakdown of respondents

Connected places, or ‘smart cities’, can be defined as a community which utilises advancing technologies to deliver services within the built environment – for example by collecting and analysing data. These technologies, which take the form of sensors, networks, applications and ‘Internet of Things’ devices have the potential to provide a range of tangible benefits to society. From a more efficient management of traffic which reduces pollution, through to facilitating efforts to save money and resources and enhancing the quality of living for citizens.

Operating within these connected places, CAM technologies providing passenger and logistics services could be designed to integrate and interact with broader digital networks to enhance the way people and goods are moved. This connectivity would

improve management of the road network by enabling real time communication between vehicles and transport infrastructure. It could improve and reduce the costs of infrastructure maintenance by using vehicles to monitor the wear and tear of roads and sharing this data with transport planners. It would enable more effective monitoring, predicting, and controlling of route demand, enabling the better design and use of public transport and space, and making our communities more attractive places to live.

The consequence of this is that the more road services depend on connectivity, the more connectivity must be considered as a part of the wider road infrastructure alongside more conventional aspects. Early planning has ensured that our key highways are equipped with substantial capacity for wired communications, and as discussed throughout section 4.3 they must continue to evolve to keep pace with the needs of users and the requirements of network safety.