Westlake Chemical’s long running battle with a slate of major insurers has morphed into one of the most consequential industrial coverage fights in recent memory.

On Thursday August 27, 2020, a fire occurred at Bio-Lab’s Lake Charles facility in Westlake, LA, according to CSB data. The company is a manufacturer of pool and spa treatment products. The company reported the release of chlorine gas as a result of the fire. There were no injuries reported but there was significant damage to the facility.

The dispute, rooted in a 2016 chlorine spill at the company’s Natrium Plant, now turns on how exclusions operate when multiple perils collide inside a tangled property programme.

And with $278 mn on the line, nobody in the market is shrugging this one off.

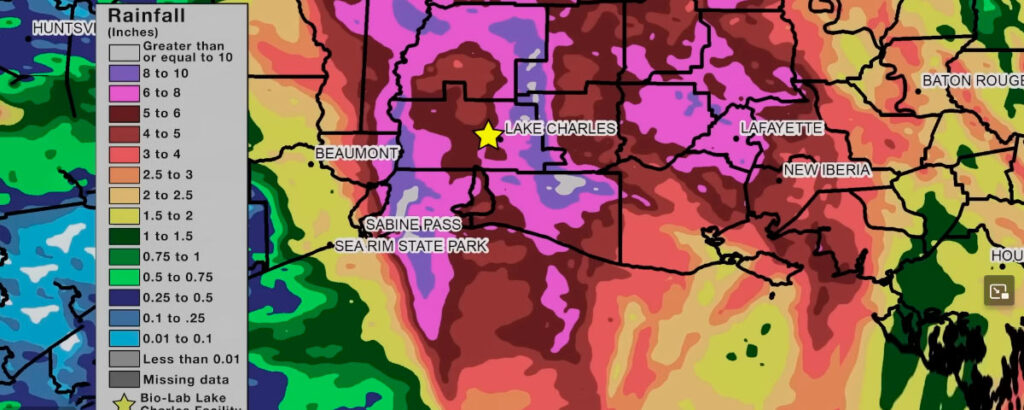

The major chlorine spill in Westlake, Louisiana, was caused by the 2020 Hurricane Laura, which damaged a Bio-Lab facility and exposed large quantities of a chlorine-based product to rainwater.

This caused a reaction, leading to a fire and the release of toxic chlorine gas that forced residents to shelter-in-place and shut down a major highway.

The incident led to a significant fire, extensive damage, and a multi-day effort to bring the chemical release under control.

The spill happened after a repaired rail tank car ruptured, releasing a huge volume of chlorine and triggering wide damage across the facility.

Westlake carried a multilayered stack of 13 policies from 12 insurers, including Allianz, ACE, Zurich, Great Lakes, XL, and National Union. After the incident, the company filed claims that climbed to $278 mn.

The insurers denied coverage, pointing to corrosion, faulty workmanship, and pollution exclusions. Westlake countered with a West Virginia suit alleging breach of contract and asking for declaratory relief, while also suing the repair vendors in Pennsylvania.

That side fight produced a $12.8 mn verdict, with $5.9 mn tied to plant damage.

The Intermediate Court of Appeals of West Virginia issued its decision on Nov. 13, and the ruling reads like a checklist of what underwriters and claims teams obsess over.

The policy form language became the battlefield: corrosion exclusion with an exception for resultant physical damage, a faulty workmanship exclusion with its own carveout, and a pollution exclusion with a conditional exception. One layer is complicated; thirteen is a maze.

The court agreed the faulty workmanship exclusion didn’t bar coverage. The spill counted as a covered peril triggered by the repair work, and the ensuing loss clause kept the door open.

On the pollution exclusion, the panel said the clause was broad and clear, but the exception preserved coverage for pollution that stemmed from a covered peril.

The one outlier was National Union’s policy, which included a tougher, stand alone pollution exclusion that shut off coverage entirely. That distinction will matter for years, maybe longer, as brokers scrutinise “similar but not the same” wordings.

Corrosion became the messiest issue. The court applied efficient proximate cause: if the chlorine spill caused the corrosion, the exclusion doesn’t apply. But there’s a factual dispute over whether some corrosion existed beforehand.

That question goes to a jury. Insurers and insureds hate this outcome for opposite reasons, but it’s the kind of turn the doctrine produces when timelines blur.

The court also rejected the trial court’s collateral estoppel finding. Damages from the Pennsylvania verdict didn’t match the policy’s measure of loss, so they couldn’t simply be imported into the insurance case.

At the same time, the appeals court affirmed the dismissal of Westlake’s bad faith claim, ruling that the insurers had reasonable grounds to contest coverage given the competing exclusion and exception language.

The result is a mix: affirmed, reversed, vacated, and remanded. The next phase includes a jury trial on corrosion cause and extent, plus recalculation of breach of contract damages.

- For insurers, the decision underlines how narrowly courts will read exclusions when resulting loss clauses sit nearby.

- For insureds, it’s a reminder that complex industrial claims hinge on sequencing, wording, and causation, not just the size of the loss.

According to our analysts, the ruling won’t stay confined to West Virginia. Insurers operating in heavy industrial markets will study this decision closely, especially those writing layered towers where one off exclusion differences can swing tens of millions.

And for buyers, the message is blunt: in a world of tight property markets and growing attritional risk, the fine print still decides who pays when the system fails catastrophically.