For re/insurance industry, digital trust and is vital for business since access to data is the key component behind risk analytics and automation capabilities. Many consumers and businesses also use the internet for commercial transactions, a trend accelerated by the lockdown days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

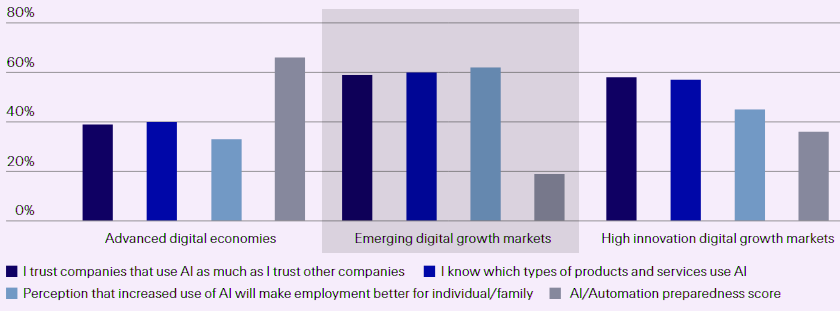

The more digitally advanced a country is, the less people trust artificial intelligence, according to analysis by Swiss Re Institute Decoding Digital Trust: A consumer perspective.

Germany, France, the UK, Canada and the US are in the top 20 most prepared for AI out of 120 countries in the study.

Trust in this technology, on the other hand, is comparatively low in these advanced digital economies, with only a third of respondents on average in each country understanding and trusting AI. The most AI-trusting people hail from emerging digital growth markets such as India, Nigeria, Mexico, Indonesia, Philippines and Argentina.

What is surprising in Decoding Digital Trust?

A consumer perspective’ is that countries with advanced levels of digital infrastructure have relatively little trust in AI. This really underlines how important it is to be transparent with customers, truly understand their needs and deliver on them.

The safety, security and efficiency of online engagements is paramount, especially in the insurance industry where customer relationships are built on trust.

Digital trust is influenced by a variety of psychological factors including cultural and generational attitudes, trust in institutions, incidence of online fraud, ease of use and understanding of technology such as AI. The report also delves into how technology such as sensors and AI/automated decision-making is closing the gap between the real and online worlds.

- Levels of digital trust are already high. The number of activities carried out in the digital space is very high, signalling already a substantial basis of trust. However, surveys suggest there is some reticence about how much data individuals might want to share, which could have significant implications as digital and real worlds increasingly overlap.

- Reluctance to share data may be driven by various factors. Willingness to share information could be influenced by factors particular to an individual, such as speed of thought or psychological type. They could also be influenced by environmental factors common to groups or nations. Speed of online decision making and data sharing also depend on amount of information available digitally, alongside factors such as user experience (UX) design.

- The correlation between digital infrastructure and digital trust is not always strong. Swiss Re Institute analysis reveals that some communities/countries with lower digital capabilities display higher levels of digital trust. This may be because elsewhere, more advanced data governance (privacy protection) and high institutional credibility generate greater scepticism.

- Cultural attitudes, ease of use and explainability of AI/automated decision making are some important factors determining digital trust. Our analysis indicates that countries with historically and culturally higher levels of interpersonal and institutional trust may enjoy higher digital trust. Ease of functionality, navigation and interoperability of digital platforms are also important. Fostering explainability in AI models is equally important to win consumer trust.

- The digital trust gap in insurance can be bridged by helping consumers feel in control of their data. This could be done by designing flexible products and solutions. Digital trust can be strengthened through transparency in data transaction, customisation and personalisation, convenience in digital interactions and, sometimes, rewards for exchange of data.

AI & IoT Technology is Closing the Gap Between Real & Online Worlds

The use of digital is rising and rising rapidly. There were an estimated 5.3 billion internet users in 2022, an increase of over 100% since 2012 (2.4 billion). The vast majority, some 4.7 billion, are on social media. Just short of 3 billion use Facebook monthly, with around 2 billion of those logging in daily. Internet users aged 16‒64 were online an average of 6 hours and 37 minutes a day in the second quarter of 2022. Time spent in the digital realm translates into hard cash. Around 89% of Americans used digital payments in 2022, spending just over USD 2 trillion.

Point made, and there are dozens of other metrics we could quote. To have achieved this level of social and economic digital penetration, suggests that a substantial level of trust between consumers and service providers already exists.

Identifying what constitutes this digital trust, however, is challenging. McKinsey categorises digital trust around four components: “confidence in an organization to protect consumer data, enact effective cybersecurity, offer trustworthy AI-powered products and services, and provide transparency around AI and data usage“.

To foster digital trust in insurance, much can be done in establishing transparency and effectively engaging with customers at every relevant touch point.

The findings of this report are a call for insurers to think about their customers’ gut feelings and how they can work with them to establish digital trust.

The key is to leverage innovative technologies that offer seamless customer experiences and make every aspect of insurance as good as humanly possible.

International Data Corporation (IDC) offers a more business centric definition based around four building blocks: Standards, Compliance and Operation, Trust Management and Connected Trust.

ISACA defines digital trust as “confidence in the integrity of the relationships, interactions and transactions among providers and consumers within an associated digital ecosystem”. PwC sees digital trust entirely in terms of business-perspective cybersecurity. All reports come to the same conclusion: getting digital trust right is good for business.

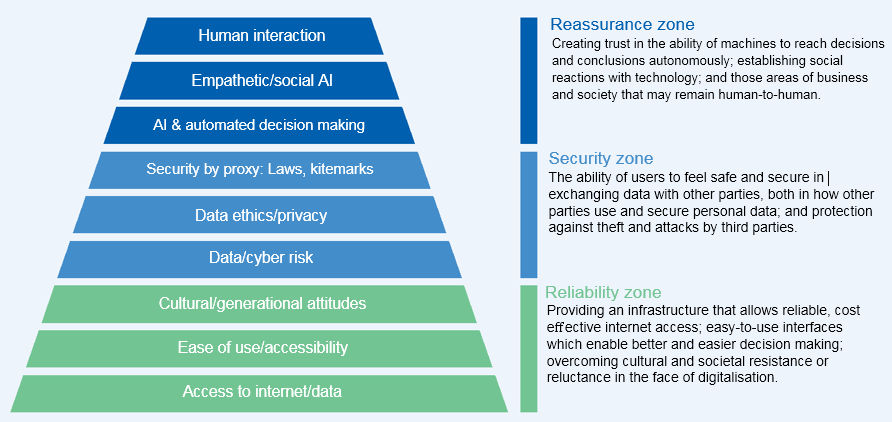

The first is reliability (access, functionality, convenience); second, security (data privacy, data ethics, secure transactions and asset retention); and third, reassurance (integrity of decision making and interaction with emotionally literate tech).

As the insurance industry increasingly improves its value chain with advanced analytics and different forms of AI, creating digital trust is essential.

The correlation between digital infrastructure and digital trust is not always strong. Hence it is not necessarily true that consumers in advanced markets are more digital than in emerging economies. It builds on two notions:

1. The digital world is increasingly blending with the physical world

The Internet of Things (IoT) will become the Internet of Everything (IoE). The ubiquitous use of sensors will take real world data into a digital realm; while AI and automated decision making will see digital processes gain real-world functions.

2. Blending of physical and digital realms presents new psychological challenges

Consumers are largely accustomed to binary on-off digital. They are the control gateway, and choose when to interact. As digital and physical blend, this control will erode. The removal of control will require psychological adjustment, which will look different according to cultural norms and backgrounds.

The IoE will provide insurers with risk data in volume and in real time. It will create ecosystems where partners can be found, solutions can be packaged and products can be retailed. All of this can be automated with AI.

It only works, however, if insurers take customers with them and create digital trust. Decoding digital trust I demonstrated how a holistic consumer perspective of digitaltrust affects the entire insurance value chain. This publication encourages insurers to take a consumer-centric view of the evolving digital world and to think through what it means to cede control.

Two-speed thinking and psychological types

In his much-quoted 2012 publication, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman, suggested that there were two forms of thought related to problem solving. System One thinking is instinctive and emotional; System Two is slower, more deliberative, analytical and logical.

Both thought systems are present in digital interactions. Teams of psychologists at tech firms have developed thousands of means to drop targeted dopamine hits to those in impulsive System One thinking mode.

Intuitive and emotional responses govern snap tweets; impulsive online buys; playing an online game one more time; searching for that kid from college on a networking site. There are around 1 billion regular users of System One thinking-centric TikTok.

Systems One vs Two thinking

System Two thinking is also part of daily life, at work, in online banking, in booking tickets, in interactions with insurers and many others. The spatial design of online platforms is a key feature influencing System Two thinking.

Systems One vs Two thinking often invokes digital information overload. This can create on-screen blind spots that can obscure important points.

With an overwhelming amount of information presented on-screen, consumers tend to think fast but not always rationally, and make System One driven online decisions that can be source of regret later. In such cases, System Two thinking could be more beneficial for consumers.

This being the case, it pays to understand some of the most important parameters of System One thinking, as defined by Kahneman:

- The human brain is lazy. When faced with a novel problem, it will seek to interpret it quickly and intuitively through previously learned encounters rather than going through the effort of analysing from scratch. Kahneman names this process heuristics and it is a means of categorising consumers biases.

- Heuristics are governed by their availability. The closer a consumer is to a particular bias, the more important it may appear.

- Kahneman finds a “pervasive optimism bias” in System One thinking that generates perceptions of control. Most individuals have an innate tendency to overestimate their ability to control events.

System One thinking helps dismantle digital inhibitions. It can allow and even encourage individuals to be generous, sometimes to the point of being reckless, with their data.

Big Tech firms sit on vast banks of data voluntarily submitted by individual users. They use algorithms to create complex psychological profiles to target products and for advertising.

The surrender of data is as impressive as it could be alarming: if stopped on the street, few would dream of telling a stranger what they might later write on the internet. So why are they willing to do so online?

The dilution of digital inhibitions is a largely System Two response, notably a perception trade-off. I surrender my data in return for something, be that free networking, search functions, maps, games, music, video, news and so forth.

User perceptions of reputation further alleviate concerns. Major tech players are established and have earned brand trust. So established have data ecosystems become, most consumers assume sufficient legal and ethical codes exist to protect their data.

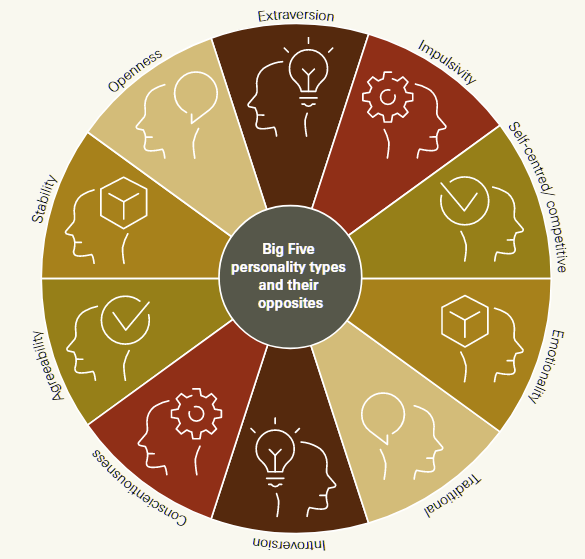

Big Five personality types and their opposites

Aside from speed of thought, another layer of individual perception that may influence how individuals regard digital trust is that of psychological type.

Digital readiness versus digital trust

This section investigates the collective rather than individual-consumer drivers of digital trust, and how AI may help strengthen macro levels of trust.

Does better digital infrastructure lead to greater digital trust?

Increasingly, being competitive in the modern world means having high levels of digital capability. Countries are establishing digital investment targets, training and education programmes, regulation, data governance structures, R&D support and initiatives, and infrastructure development. Intuitively, greater digital capacity would signal greater digital trust.

Not necessarily so. The correlation between digital trust and development is not always strong. The IMD World Digital Competitiveness Report measures the capacity and readiness of 63 economies to adopt and explore digital technologies.

The top performers in 2022 were Denmark, the US, Sweden, Singapore and Switzerland. The three sub-factors compiled by the digital competitiveness index are:

- Knowledge: technical know-how to discover, understand and build new technologies.

- Technology: overall infrastructural environment enabling the development of digitaltechnologies.

- Future readiness: level of country preparedness to exploit digital transformation.

We tallied these digital competitiveness rankings against the digital trust index rankings published by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR).

This latter study assesses the gap between consumer attitudes towards online and digital services, and levels of trust typical of societies in different countries.

The report finds a positive trust gap for non-western markets (with lower digital readiness) compared to western markets (with advanced digital capabilities). The digital trust index is built using data assessing consumer experience of online and digital services. Factors that result in lower trust include online fraud and personal data breaches, lack of transparency or poor reputation of digital service providers.

Digital trust pyramid

Digital trust pyramid dimensions: Digging deeper

Our quantification process begins by using four to six alternative parameters as proxies for each of the nine dimensions (total of 46 parameters), for a total of 120 countries, and assess their robustness.

For example, access to data can be measured by parameters such as individuals using the Internet (% of population), fixed broadband subscriptions (per 100 people), and share of population with 4G mobile network coverage.

We can subsequently check on feasibility and data consistency to narrow our analysis down to the most suitable signals.

For the parameters included within each dimension, we create a weighted average index for each of the nine dimensions for all the countries analysed. We then use these standardised country specific dimensional scores to group countries into clusters. We created four clusters of countries with similar digital trust qualities.

The purpose of this exercise is to identify the factors that have the highest explanatory power in determining digital trust, globally. Though all the nine dimensions are important, some may fuel accelerated growth in digital trust.

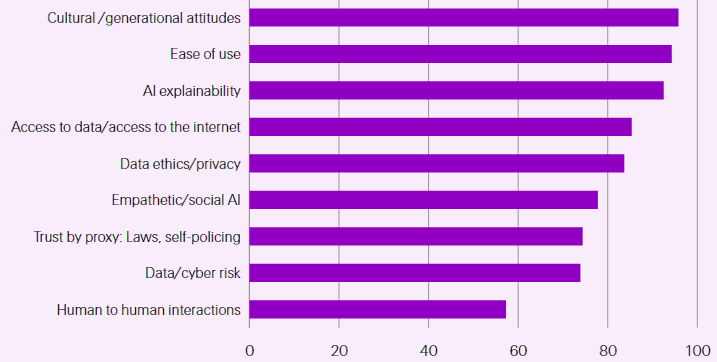

Our analysis reveals that the three most important dimensions are cultural and generational attitudes, ease of use and explainability of AI/ automated decision making.

Cultural and societal attitudes rank highly in our analysis with an ability to contribute up to 95% of variance in digital trust between country clusters. Scandinavian countries outperform in terms of digital trust scores. The reason may be rooted in their history and culture. These countries have historically displayed higher levels of interpersonal trust and trust in their institutions (including when they collect data). This may also translate into higher levels of digital trust.

They also have deep belief in transparency, social and environmental responsibility and are therefore more willing to lend digital trust to businesses and institutions that are perhaps driven by a sense of purpose, and not profit alone. Countries with high levels of societal trust tend to do better with digital trust.

Relative importance of digital trust themes

Cultural barriers on the other hand may impede digital trust and societal cooperation. Such barriers include an inherent risk aversion, fear of change, hierarchical decision-making, and political and institutional inertia.

Ease of use is the second most important factor according to our variance analysis, explaining more than 94% of the variation in digital trust. The importance of perceived ease of use in strengthening digital trust is well documented.

Digital platforms should allow for ease of functionality, navigation and search, along with features such as portability and interoperability.

One study finds ease of use as measured by ease of recognition, ease of navigation, ease of obtaining information and ease of purchase as positively influencing digital trust in e-banking platforms.

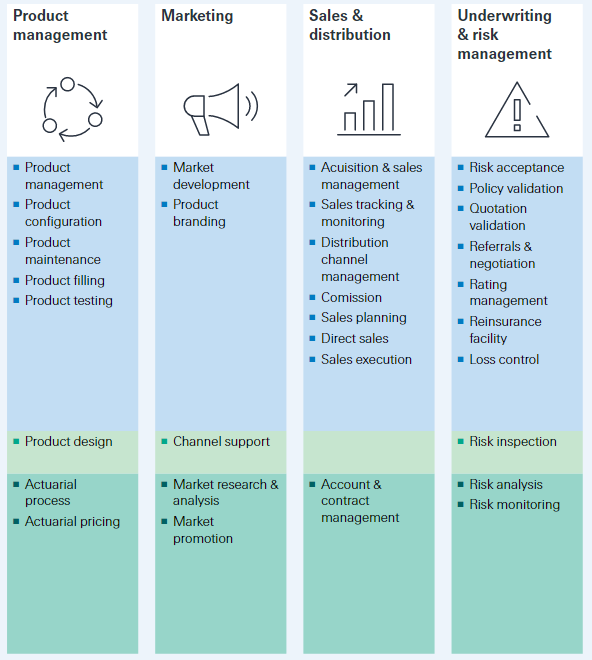

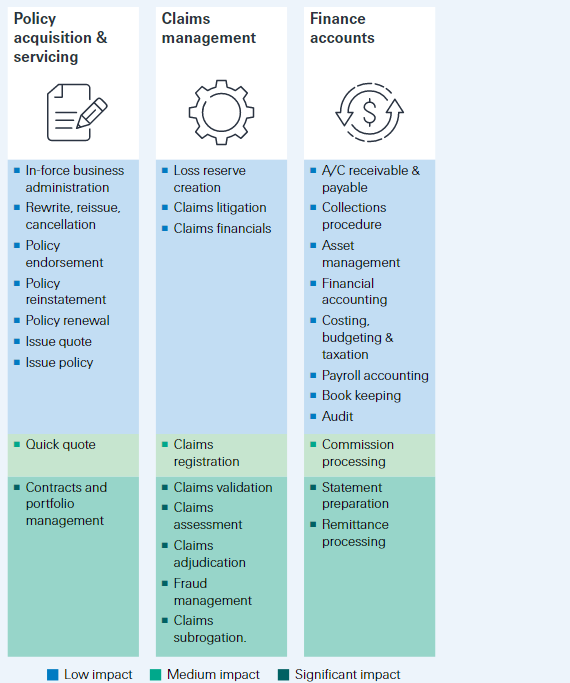

Opportunities for AI in insurance

Advanced analytics and some forms of AI have been enriching the insurance value chain for several years and will have a different impact on each stage of the chain in the future.

The relative impact of AI across the insurance value chain

AI enables re/insurers to become more efficient and offer new solutions, but for that an entire system is required for its use, including human interaction.

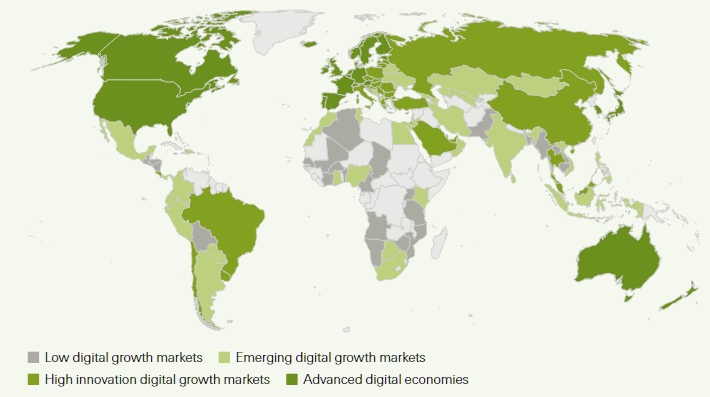

Swiss Re separate 120 countries into four clusters: low digital growth, emerging digital growth, advanced digital, and high innovation digital growth markets

The added value of AI therefore only comes from the smart combination of AI models and human processes, not a standalone AI model in isolation.

Country clusters and attitude/perception of AI

Digitally-similar country clusters

Anticipating a loss of control

Both individual and environmental factors can shape digital trust. Together with providing transparency, understanding, a clear explanation of data needs and requirements, insurers can also consider how to create mechanisms that build digital trust around cultural and psychological factors. Some suggestions as to how they could achieve this include:

Giving back control

As we identified in Section One, many consumers feel more secure when they feel they are in charge of their data. One means of promoting this perception is to allow consumers to proactively select what data they are willing to share with their insurer.

Some may be comfortable with health data but not their GPS location data; others exercise but not driving data. And, if the consumer wants to turn off all tracking functions, that should be respected.

The challenge for insurers will be to create products that can adjust to different levels of willingness to share data, and the parameters as to when a consumer can set or adjust their willingness to share.

Transparency

All products come with terms and conditions (T&Cs). However, many consumers do not have the time or desire to read the T&Cs. Isolating the key variables in the T&Cs, and presenting them as simply as possible, will increase trust. Explaining when and how data will be anonymised can also help.

Re-set options

Ignoring reasons for lack of digital trust may facilitate development of a negative feedback loop. Consumers could become wary of business and equally, business may be fatalist about interacting with unresponsive consumers.

The best means to combat this, in our view, is a dramatic gesture – may be a one-off gift – that can take the initiative, break the negative loop, and start constructive dialogue.

Customisation

Different psychological types will feel more comfortable with different forms of interaction. One way to facilitate this is to allow them to develop a front end they are comfortable with. Some individuals will want to see all their data to create their own analysis. Some may be motivated by gamification, competing with others or just themselves.

Some may not wish to see their data at all (but are OK with it being tracked). There are health trackers in jewellery, negating constant presence of a screen. The perception of being able to steer product interaction will enforce the perception of control.

Convenience

Convenience is the ultimate friend of the lazy brain and System One thinking. In most cases, the easier it is to sign up to a product, the happier the consumer. But perhaps not in all cases.

Too much convenience may worry some individuals that they are moving too fast. Many now feel they have drifted into subscriptions for products they did not really want. This has attracted the attention of authorities who fear mis-selling. Allowing time for some pause and reflection for the consumer could be beneficial.

Financial rewards

One carrot to provide encourage data sharing is some form of compensation. In the insurance context, this is most likely in the form of premium discounts.

The hope is a discount prompts consumers to calmly consider what price their data is worth. Yet, it seems relatively few would accept a premium trade-off for tracking devices from their insurer.

For example, in a 2022 survey, 68% of respondents in the US said they would never accept a premium discount from their insurer for a house/ health/ driving tracker. Of the minority that might consider trading data for a premium discount, 67% stated it would need to be at least 50%.

Personalisation and marketing

Personalisation marketing is enough of a stand-alone concept to earn its own Wikipedia page and is described as “one-to-one” or “individual marketing”. An Internet of Everything combined with AI has the scope to tailor highly individual product and service offerings to individuals.

Personalisation is a double-edged psychological sword. Certain types in certain situations will be very receptive to highly personalised communications. It will encourage their trust.

Others may be repelled. The idea that either their insurer, or the algorithm employed by their insurer, knows them well enough to provide personalised offers may be perceived as troublesome or even sinister.

Insurers therefore need to be sensitive in using personalisation marketing. One way would be to ask policy holders if they would like a proposal to match their needs rather than coming to them unsolicited.

Another might be to open a dialogue with policy holders, asking and involving them in the process, rather than present them with an already completed offer. A third may be to have a human agency layer on top of AI architecture to reach out to those customers more comfortable with in-person communications

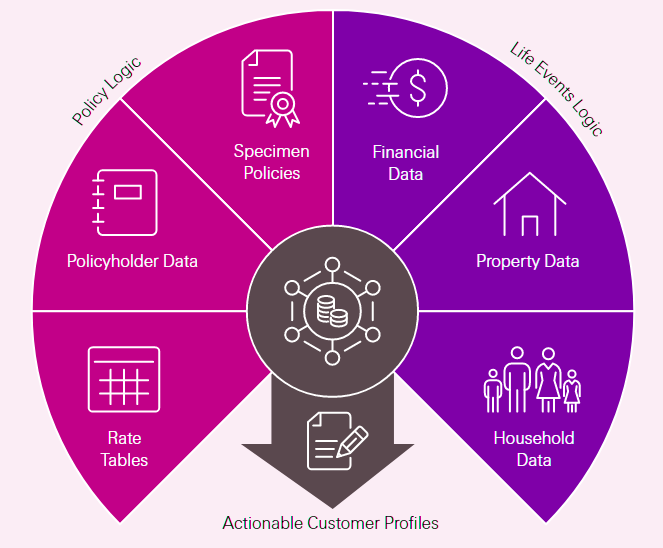

Data sources enabling better customer outcomes

In the ecosystem

Insurers can help develop trust as part of a wider network. A data sharing package of services around health, for example gym membership, health care services, health and life insurance, even rescue services might reduce consumer impulsivity in terms of data sharing, and encourage them instead to consider the holistic value of the offer.

Some insurers are already offering engagement platforms in the life and health sphere. Similar packages could be constructed for driving and potentially for property insurance.

The notion of ecosystem delivery of products and services has been around a few years; their realisation has thus far only been partial. The challenge is that various component parts of potential ecosystems have been developed with heavily segregated data channels and sensors that may not talk to each other.

Embedded Insurance

Embedded insurance is the integration of insurance at the point of sale of a good or service. Travel insurance can be sold next to holidays; driving insurance next to cars, and so on. Embedded insurance not only offers convenience and choice for customers; it also provides rich and valuable data for insurers and partners.

The customer experience should be at the forefront of every step in the value-chain. To achieve a single view of the customer, there is no room for friction between technologies, systems and partners in an ecosystem. Embedded insurance revenues in Europe were reported an estimated USD 11 billion.

Conclusion

Psychologists, philosophers, marketing professionals and novelists have long sought to tackle the issue of trust. Trust in a digital realm is an emerging discipline, one largely governed by consultancies and business writers. They have largely presented trust as something embodied in System Two thinking.

Trust comes in considered reflection, when individuals and interfaces are open, transparent, clear in their intentions and iterating the mutual benefits of trust in the digital realm.

All of this is, as we have discussed, valid. However, other factors in trust exist. The multidimensional approach to thinking about how customers perceive trust at different steps of the customer journey will be a crucial part of the puzzle in our evolving digital world.

The Internet of Everything and the pervasive use of AI will make new demands on consumer psychology. The opportunities are clearly considerable; but will require empathy. Gut feelings, cultural heritage and environmental markers are factors as strong in decision making as clear thought. All are required for trust.

…………….

AUTHORS: Simon Woodward – Senior Content Developer & Editor, Swiss Re Institute, Mitali Chatterjee – Insurance Research Manager, Swiss Re Institute, Nikhilmon O U – Research Analyst, Swiss Re Institute

CONTRIBUTORS: Jonathan Anchen, Francesca Tamma, Michael Föhner, Luca Baldassarre, Yannick Even, Mary Bourke Stöckle – Swiss Re Institute