The increase in interest rates over the last year has been positive for life insurers in Europe, improving both solvency and financial results. However, the fast pace of the increase means that most insurers are sitting on significant unrealized losses in their fixed income portfolios, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

This creates a risk, as illustrated by the recent distress of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in the US. However, we do not expect insurers’ unrealized losses to crystallize.

This is because they are generally able to hold fixed income assets to maturity as a result of their sticky, long duration liabilities, and because of their sound asset liability management (ALM).

Higher rates have also led to derivative collateral calls, which remain manageable.

Material realization of investment losses

The strong rise in interest rates in 2022 led to a significant decline in the value of fixed income investments, which form the majority of insurers’ portfolios. The fair value of these investments is now in most cases below their acquisition cost, i.e. in a position of unrealized loss.

Higher rates have generated significant unrealized losses against insurers’ fixed income portfolios. In general, we expect insurers to hold their assets to maturity.

This reflects the illiquid nature of some of their liabilities, with customers unable to withdraw funds on demand or incurring a penalty if they do so. Insurers’ asset liability management is also sound.

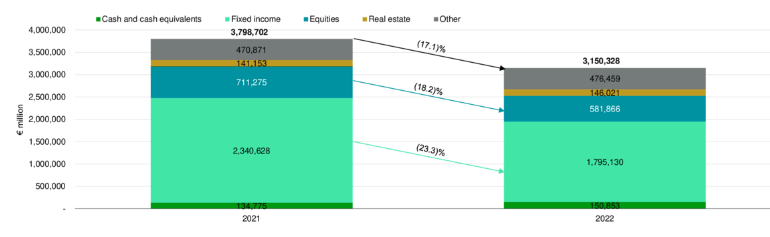

Investment portfolios fell significantly in value during FY 2022

We do not expect these losses to be realized. This is because insurers have a relatively illiquid liability profile, and practice sound asset liability management (ALM). They are therefore generally able to hold their investments to maturity, by which time losses will have reversed.

Insurers are typically cash rich because they receive customers’ premiums before paying claims. This limits the need to sell assets. Moreover, insurance liabilities tend to be “sticky”, both in the property and casualty (P&C) and life sectors.

For example, some life policies, such as lifetime annuities, are fully illiquid and cannot be surrendered (see Life Insurance Industry Results). Customers can surrender other types of life policy, but in many cases they would incur penalties or fiscal charges as a result. This may deter many policyholders from lapsing.

In addition, ALM is at the heart of the insurance business model. To a large extent, insurers manage their assets and liabilities interdependently.

When insurance policies (liabilities) reach maturity, there are generally corresponding assets that mature at or near the same date.

Insurers typically put these matching assets in place at the inception of the policy, which reduces the need to sell assets at depressed prices to meet claims during periods of market stress.

Insurers often carry a negative duration gap, holding assets of shorter average duration than their liabilities, providing them with more asset flows to face liability outflows.

This partly reflects a scarcity of high quality liquid fixed income assets that match the long duration of insurance liabilities. However, many insurers also choose to maintain a negative duration gap, as this allows them to accommodate a potential increase in lapses, which reduces the average duration of their liabilities.

Insurers also hold liquidity buffers to cover stress scenarios, including a potential increase in surrenders, and have undrawn emergency liquidity facilities.

Under Solvency II and equivalent capital regimes, insurers must also hold sufficient capital against lapse risk to cover losses (including investment losses) in a 1-in-200 year event (see TOP Global Reinsurers by Country).

While liquidity and asset liability management varies across European insurers, we do not expect even severe stress to lead to the failure of any large and well diversified players. While some companies sold investments at a loss to stay within their liquidity risk appetite during 2022, these disposals fell within their usual liquidity management procedures.

More concentrated insurers with specific liability profiles and narrow distribution strategies and client bases may be more exposed.

However, we see insurers as much less vulnerable to a “run on the bank” scenario than banking institutions, which by design usually operate with a large mismatch between assets (long-term loans) and liabilities (which include short-term deposits that can be withdrawn on demand, and confidence-sensitive wholesale funding).

Lapse risk increasing but still low

Genuine economic losses would emerge if insurers had to liquidate investments sooner than expected. A mass lapse, where a high proportion of customers surrender their policies over a short period of time, would be the most likely cause of such losses.

Since the design of many life insurance products make surrender financially disadvantageous or even impossible, we see such an event as unlikely.

Insurers are most exposed to lapse risk through their portfolios of traditional savings products, which offer guaranteed rates of return. In most jurisdictions, these products expose insurers to potential investment losses.

Meeting the liquidity demands of a mass lapse would involve selling fixed income investments and realizing fair value losses.

Lapses of unit-linked portfolios do not directly expose insurers to investment risk, as policyholders bear the investment loss in full.

However, the consequent decline in insurers’ assets under management would put pressure on their fee income. The lapse of profitable policies also reduces future profitability, and means policyholder acquisition costs may not be recovered.

Higher rates and reputational issues increase lapse risk

Higher interest rates increase lapse risk as policyholders’ returns on existing insurance products may become less attractive than those of newer investment products, including those offered by banks.

Because of the long duration of insurers’ assets, investment returns, and therefore rates credited to policyholders, will only gradually increase (see TOP 25 Largest Insurance Companies in the World by Assets).

In contrast, non-insurance savings products or newer insurance policies will immediately offer rates of return that reflect the current level of interest rates.

Currently, we do not believe the difference in remuneration between banking and insurance products is high enough to trigger a significant increase in lapse rates. Policyholders with older insurance savings policies may still benefit competitive guaranteed rates, and will hence have little incentive to switch.

Insurers also have the option of increasing credited rates for customers holding policies with lower guarantees, helping them remain competitive. In France, for example, companies have been increasing deferred profit-sharing reserves for this purpose.

A further sharp increase in rates could however expose insurers to the risk of a significant increase in policy surrenders.

Lapse risk depends on product mix and features, distribution, client base

In the unlikely event of a mass policy surrender, French and Italian insurers would be more exposed than other European peers. This is because they focus on savings products which are easier to surrender than in other countries.

While many jurisdictions impose steep surrender penalties and market value adjustments on policyholders that liquidate their contracts before maturity, these penalties are low or non existent after a few years in France and in Italy.

Conversely, UK insurers write high volumes of annuities, which cannot be surrendered. In addition, some UK with profit savings policies allow for market value adjustments and the forfeiture of terminal bonuses on early surrender. These mechanisms are a deterrent to policy lapses.

Beyond these market-specific considerations, insurers’ product, distribution and client mix are important factors that influence their exposure to lapse risk.

For example, many French and Italian insurers have diversified their product mix, growing into unit-linked and protection, which reduces their overall exposure to lapse risk.

Protection is usually not subject to surrender risk, while unit-linked business does not expose insurers to investment risk.

Control over distribution channels is also key to retaining customers. Proprietary networks, such as tied agents, salaried sales forces or affiliated banking networks, are widely used across Europe, and tend to be more efficient in retaining clients.

These networks have strong incentives to retain clients as their interests are aligned with those of the insurer. Conversely, lapse risk is higher for insurers that do business through brokers, financial advisors, or non affiliated banking partners.

A non affiliated banking network may for example have some interests in advising its client to switch from an insurance product to a banking product.

The companies targeting corporate customers or affluent and financially sophisticated retail clients are more exposed to lapse risk.

Such clients are more likely to reallocate their savings when financial conditions change, or if doubts over the financial condition of an insurer emerge. In contrast, mass retail clients have historically proved to be very sticky customers.

Customers will also consider the potential loss of tax advantages, which continue to support the sale of some insurance products in many countries (e.g., France, Germany), before redeeming their policies.

Derivative collateral calls manageable

Many interest rates hedges put in place by life insurers fell out of the money in 2022 as a result of rising rates, forcing them to pay collateral to keep their positions open.

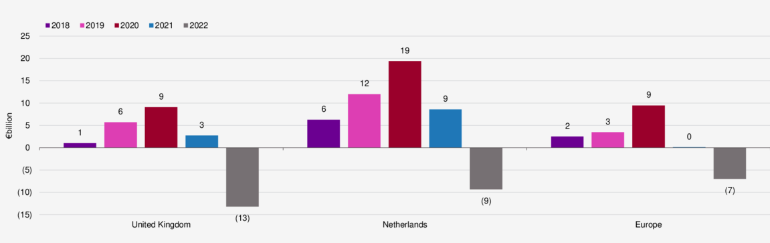

Insurers in the UK and the Netherlands, which make widespread use of derivatives for duration matching, were most affected.

The industry has however weathered collateral calls without resorting to forced sales or emergency measures.

Net reported fair value of derivatives at year-end 2022 (EURbn)

In contrast, many UK pension funds were forced to sell assets in September 2022 after the UK government announced large unfunded tax cuts, triggering a spike in gilt yields.

This is partly because pension funds were allowed to remain underfunded (i.e. the present value of their assets was less than the present value of their liabilities) during the low interest rate era, and they therefore lacked sufficient liquidity buffers to absorb the shock.

Insurers, however, were required under Solvency II and equivalent capital regimes to maintain a capital surplus against various 1 in 200 year stress events, which provided a capital buffer.

Diversification and strong liquidity management also contributed to insurers’ resilience. The sector holds surplus liquidity to cover stressed scenarios at a high return period (typically a 1 in 200 year shock).

An additional mitigant was insurers’ use of over the counter (OTC) rather than exchange traded derivatives. While exchange-traded derivatives demand cash collateral, a broader range of assets is eligible as collateral against OTC derivatives.

As a result, insurers do not need to sell assets to generate cash to collateralize their positions.

Selling assets to generate cash would crystallize currently unrealized losses, whereas posting them directly as collateral means insurers can continue holding them to maturity.

Reductions in the value of non-cash collateral assets would lead to top-ups being required, but insurers hold a significant amount of good quality assets eligible as collateral.

Life insurers’ hedging positions are long-dated, in line with their long term liabilities. In the Netherlands we estimate that more than three-quarters of derivative contracts are due to mature in more than 5 years time and around two-thirds in the UK, although less than half for European groups.

Collateral requirements will therefore not materially reduce over the medium term, unless interest rates fall.

……………..

AUTHORS: Will Keen-Tomlinson – VP-Senior Analyst Moody’s Investors Service, Benjamin Serra – Senior Vice President Moody’s, Simon James Robin Ainsworth – Associate Managing Director Moody’s, Antonello Aquino – Associate Managing Director Moody’s, Sebastian Pfeiffer – Associate Analyst Moody’s