The concept of financial wellbeing recognises the link between the general wellbeing of individuals and the availability of sufficient resources throughout the life course to meet ongoing financial obligations and achieve future financial aspirations.

While ensuring financial wellbeing is the core purpose of life insurance, traditional business models have come under stress as socio-economic, demographic, health and technological developments, combined with a protracted period of low interest rates, have dented the appeal of savings-oriented life insurance globally.

Not only has this gradually eroded the financial wellbeing of individuals, it has also raised questions about how the life insurance business should evolve in the future.

Global life expectancy has risen by six years in the past two decades and is projected to rise by another eight years to 81.7 by the end of the century. In Europe and Japan it is expected to reach 88.8 and 93.5, respectively.

The findings underscore that retirement insecurity is growing. In developed countries, ageing populations and slower economic growth are undermining the sustainability of the near-universal state pension systems that were established or expanded in the early post-war decades.

Life insurance industry helpes individuals and families meet their goals

If the life insurance industry is to help individuals and families meet their goals, it will have to provide a range of new financial wellbeing products and services alongside retirement savings and protection.

According to The Geneva Association Report Financial Wellbeing, also highlights the role that trends in the health of the elderly are likely to play in driving up healthcare expenditure and undermining financial wellbeing. Almost 60% of people aged 65 and over in OECD countries now report living with two or more chronic health conditions. While the level of observed disability among the elderly has fallen in recent years, helping to facilitate longer working lives, age-specific rates of chronic morbidity have been flat or rising at older ages, which suggests that the underlying health of the elderly is not increasing in tandem with life expectancy.

The fact that the incidence of chronic illnesses among younger adults is now rising in some developed countries is also a cause for concern and could put additional pressure on health and care budgets, undermine productivity and reduce wealth accumulation across the life cycle. Reversing these trends will require timely preventive health interventions with a focus on the most vulnerable, who tend to be people on lower incomes and with lower educational attainment.

Retirement savings remain inadequate almost everywhere, with many facing impoverishment in old age.

Most insurers agree that financial wellbeing should be considered comprehensively, but their emphasis remains on retirement savings. There is widespread consensus that demographic shifts in particular are driving the concept and shaping their market. Surprisingly, technological drivers are seen as less important, except as an enabler of more sales, better marketing and improved access. Insurers and banks are viewed as the most active players in this space, followed by governments. Notably, independent (digital) platforms are seen as one of the least active players.

All insurers offer products to enhance financial wellbeing that go beyond traditional risk and savings solutions. Most financial wellbeing products are designed with retirement security as a primary goal, followed by financial literacy and encouraging general savings. Intriguingly, limiting risk exposures through more preventive strategies is the least cited motivation.

Financial management, including tackling debt, falls outside the scope of the products offered by insurers, suggesting that insurers are largely working within the parameters of their traditional roles while taking some incremental steps to influence other financial behaviours (see Financial Security Worries and Appetite for Digital Insurance. Consumers Surwey).

Product characteristics appear to mirror these findings, as does their target demographic. Few insurers focus on the young with financial wellbeing programmes, with the vast majority focusing on working-age adults and only some aiming at those aged 65 years and over.

Most insurers deem financial wellbeing products to be successful in increasing customer numbers, retention and experience. There is an acknowledgement that more needs to be done to increase the number and improve the quality of touchpoints with customers to boost engagement and influence behaviour.

As far as consumer outcomes are concerned, there is a widespread belief that life insurers are well-positioned to enhance financial wellbeing, especially by moving towards better customisation of products, reframing retirement savings goals as part of general savings goals to counter low prioritisation of insurance and tapping into the needs of the elderly with better integration of healthcare services.

Life insurers can enhance financial wellbeing, including by reframing retirement savings goals as part of general savings goals.

However, life insurers also face important challenges, including the squeeze on household disposable income, which makes it difficult for people to achieve meaningful savings, and the volatility of the political and regulatory environments, which makes it difficult to instil long-term savings habits.

How Are Life and Endowment Insurance Similar?

Life and endowment insurance policies are most similar in their structure. You can have either policy as either a term policy or a whole life policy. A term life policy is a policy that you keep over a set number of years. When the plan matures, you will either get a payout or your policy will end. A whole life (or whole of life) policy means the policy will be in place until you pass away. When it comes to whole life endowment and life insurance, your beneficiary will get the lump sum payout.

Both insurance policies can be participating, meaning that both endowment and life insurance plans will accumulate cash value and provide a non-guaranteed bonus that comes from your premiums being invested in the insurer’s fund.

At the end of the policy term, the payout will be the sum assured and any accumulated bonuses or cash dividends. However, this means that both endowment and life insurance policies will also be subject to early surrender fees and will require you to hold on to the policy until it matures to avoid losing money.

The premium structure is also similar. For both whole life insurance and whole of life endowment policies, you will pay premiums monthly or annually up until the policy matures. For term life and term endowment policies, you will pay premiums for a certain number of years or until a certain age. Both endowment plans may also offer the opportunity to pay a single premium upfront. The main difference between endowment and life insurance is that some endowment policies are limited-pay policies, which means that you will pay premiums for a shorter time period than your policy term (i.e. you pay policies for 3 years but your policy matures in 10).

How Are They Different?

The major difference between life and endowment is that they have two different end goals. Life insurance covers you mainly for death, terminal illness or disability while endowment is more of a savings plan with a small life insurance component attached.

The time period for these policies are different as well. While both life and endowment policies can be either term or whole life plans, endowment plans typically have a shorter term period. Endowment plans have maturity periods between 3 to 25 years, while term life insurance plans mature either after 20-25 years or up until you turn a certain age (ex: up to age 55, 60, 65). Term life insurance policies may also give you the option to convert to a whole life policy, something that a few endowment plans may let you do as well.

The payout is also different. Endowment policies are created to give you, the policyholder, a payout when the policy matures.

They can also provide annual cash benefits or act as supplementary retirement income. On the other hand, life insurance policies will payout to your beneficiaries. Even if you have a term life policy, you won’t get a payout if you survive after the policy matures.

Furthermore, as you pay into an endowment policy, your premium will be split between contributing to the savings portion and to the life insurance portion. Because of this, you may encounter endowment policies whose guaranteed payouts are less than the total premiums you invested into the plan. If the fund performed poorly as well, you may even end up losing money. On the other hand, life insurance policies guarantee your sum assured so your beneficiaries are guaranteed to get at least that amount when you die.

The declining appeal of savings-oriented life insurance has eroded people’s financial wellbeing and raised questions about how the life insurance business should evolve.

Average global life expectancy has risen by six years in the past two decades alone and stands at 73.3 years. The UN Population Division projects that it will rise by another eight years by the end of the century to 81.7, and that in Europe it will reach 88.8 and in Japan 93.5.5

Some experts project still larger gains, with a few even suggesting that babies born in Europe today can expect to live to the age of 100.6 Irrespective of which projections one accepts, one thing is clear: Longevity is no longer the exception for a lucky few, but a clear cut and predictable experience for most.

Capturing the opportunities associated with longevity will require a more integrated and holistic approach to financial wellbeing, with important implications for life insurance.

Life insurance and financial wellbeing

The main purpose of insurance, and specifically life insurance, is to promote financial wellbeing by cushioning shocks from death or disability while enabling retirement savings. However, the demographic and socio-economic environment is changing in ways that have made it more difficult for life insurance to fulfil its purpose effectively.

According to Report Global Insurance Markets Trends and Forcasts for Life Insurance, dynamic and less secure labour market, rapid ageing, the epidemiological shift from infectious to chronic diseases and the rise of the digital economy are among the most important disruptive forces.

Views about what constitutes financial wellbeing have also evolved to become more holistic, and the concept now encompasses a broad spectrum of life events that are both financial and non-financial in nature. It is not just physical health that concerns people today, but also mental health.

It is not just preparing for retirement, but also achieving better work-life balance.

Despite the changing environment, life insurance products have broadly remained the same. This inertia, coupled with a protracted period of low interest rates (more recently being exacerbated by surging rates of inflation), has dented the role of traditional life and retirement products as a key contributor to financial wellbeing. Reversing this trend may require revisiting the fundamentals of the industry’s business model to match it with the more varied and dynamic needs of today’s population.

Life insurers will need to move away from one-off sales of policies with fixed premium payments to more flexible propositions.

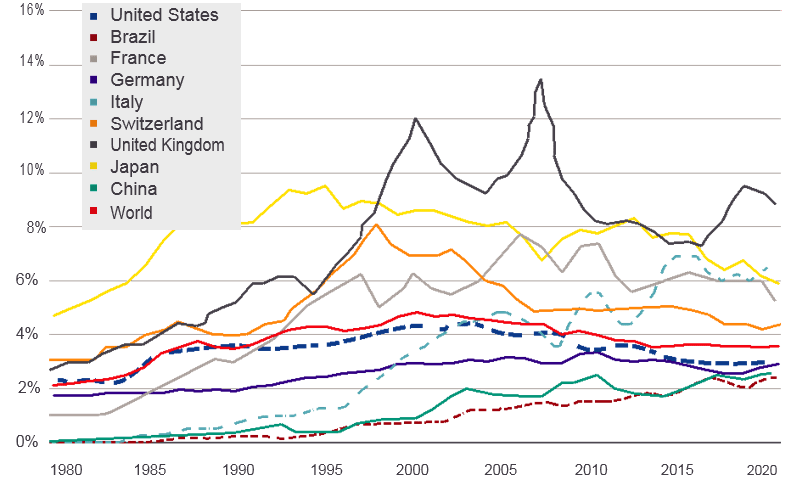

To be sure, the industry has taken some steps to adapt to the new realities by enhancing existing customer propositions, offering new ones, improving retention and adopting new risk mitigation/preventive measures. However, these steps, some of which will be discussed later in the report, have failed to arrest the steady decline in global life insurance penetration, i.e. life insurance premiums as a share of GDP, over the past two decades. This decline has especially affected savings-oriented and longevity protection products such as endowments and annuities.

Life insurance penetration (premiums as a share of GDP)

While life insurance penetration has continued to grow rapidly in developing countries such as China and Brazil, it has declined dramatically in most advanced economies. In both the United States (U.S.) and Japan, life insurance penetration has fallen back to levels last seen about 35 years ago. In the United Kingdom (U.K.), Germany and Switzerland, the set-backs amount to 20–25 years.

While some life insurers have made headway on digitalisation, the industry as a whole has been slow to capitalise on technology to advance its position.

Life insurance in France initially proved more resilient, yet after the Global Financial Crisis penetration receded to levels last seen at the beginning of the century. Italy is an outlier among the mature insurance markets, registering a massive increase in life insurance penetration over the past four decades. Experts attribute this phenomenon to insurers’ much greater resilience during the financial crisis compared to the banking sector, as well as to sharp declines in historically elevated inflation rates.

The changing environment for retirement

Retirement institutions are under mounting stress around the world. In many developed countries, the pressure of ageing populations on national budgets has compelled governments to enact large reductions in the future generosity of state pension systems, which are the main source of income for most retirees.

In many emerging markets, the traditional model of family-centred old-age support is weakening as countries develop and modernise, yet formal government and market substitutes are not yet fully developed. Almost everywhere retirement insecurity is growing, and along with it the need to broaden and deepen long-term savings and insurance coverage.

What future generations may look back on as the golden age of retirement may now be coming to an end in the developed world. Beginning in the early post-war decades, the establishment and expansion of state pension systems transformed retirement from the aspiration of a privileged few into a near-universal life cycle phase. Along with rapid growth in private pension coverage in some countries, these systems also helped to bring about a dramatic transformation in the economic status of the elderly.

The main problem in the developing world is that in economies with large informal sectors the reach of state pension systems is often limited

The prospects for future retirees are not as bright. In recent decades, falling birth rates, rising life expectancy and slower economic growth have undermined the long-term sustainability of the developed world’s state pension systems, most of which are financed on a pay- as-you-go basis, and governments have responded by reducing their generosity.

The vulnerability of retirees of course varies tremendously not just between countries, but within them. Not surprisingly, lifetime low earners also tend to have low incomes in retirement, though in most developed countries and some emerging markets progressive benefit formulas, means-tested supplements or non-contributory ‘social pensions’ help to lift them out of poverty. In most countries, the ‘old elderly’ in their eighties and beyond have lower incomes and higher poverty rates than the ‘young elderly’.

Everywhere, women are at greater risk than men of exhausting their savings because they typically earn less, are more likely to cycle in and out of the labour market and live longer

Everywhere, moreover, women tend to be more vulnerable than men because they typically earn less, are more likely to cycle in and out of the labour market and live longer, which puts them at greater risk of exhausting whatever savings they have.

Private pensions and personal retirement savings

There are two ways to boost retirement incomes without putting an additional burden on government budgets or families, the first of which is for workers to save more for retirement over the course of their working lives. Some developed countries have always leaned heavily on employer pensions or personal retirement savings to supplement or even substitute for state retirement provision.

What has changed is that countries throughout the developed world are making concerted efforts to broaden and deepen retirement savings systems, including some that have relied almost exclusively on pay-as-you-go state pension provision in the past.

Italy and South Korea are in the process of replacing their traditional unfunded severance pay schemes with genuinely funded pensions.

The U.K. has launched a new retirement savings scheme called NEST Pensions, while New Zealand has launched a scheme called KiwiSaver. Many emerging markets are also trying to expand retirement savings. In an especially promising development, their efforts are often focused on informal-sector workers, who currently must rely on their grown children for support in old age or, if they are fortunate, a non-contributory social pension.

Advances in digital IT, financial inclusion and national identification systems are opening up new ways to extend participation in retirement savings programmes to informal-sector workers.

Some countries are employing financial incentives, such as matching contributions, to encourage them to participate on a voluntary basis in formal-sector retirement savings systems. Others, including China, India, Malaysia and Thailand, have launched separate contributory retirement savings systems with more flexible contribution and withdrawal rules that are tailored to the needs of informal-sector workers.

Some of these recent initiatives have been highly successful. Pension coverage has risen substantially in New Zealand and the U.K. over the past decade, in large part because both countries, leveraging the lessons of behavioural economics, have adopted an auto-enrolment model in which workers, instead of having to proactively opt into the pension system, have to proactively opt out.

Ensuring adequate retirement savings is being complicated by the replacement of traditional defined-benefit plans with defined-contribution plans

Participation in India’s new informal-sector retirement savings programme, the Atal Johana, has also grown rapidly, as has participation in China’s two new informal-sector retirement savings programmes, one of which is for rural workers and one for migrant workers.

Longer working lives and later retirement

The other way to boost retirement incomes is to work longer. All other things being equal, if workers contribute for five more years to a defined-contribution retirement plan, and collect benefits for five fewer years, the plan’s income replacement rate would be roughly one third greater. In addition to the financial benefits of longer working lives, there may also be health benefits.

A growing literature suggests that continued productive engagement can have a large positive effect on the physical health, cognitive function and emotional wellbeing of older adults.

Implications for long-term savings

All of this points to a straightforward conclusion, which is that long-term savings will be an increasingly important part of the retirement equation in decades to come. In the developed world, future retirees will not be able to count on state retirement provision to the same extent that today’s retirees do, while in the developing world they will not be able to count on the family to the same extent.

Along with the erosion in these traditional pillars of retirement income support, longer working lives and rising life expectancy will also tend to buoy up savings.

Long-term savings will be an increasingly important part of the retirement equation in decades to come

Another trend may be increased demand for flexible long-term savings products that allow workers to access retirement savings for purposes other than retirement. People are not only working longer and retiring later, but retirement itself is also becoming a more malleable concept, especially for better educated workers: flexible retirement, phased retirement and unretirement are all gaining in popularity.

Economic drivers

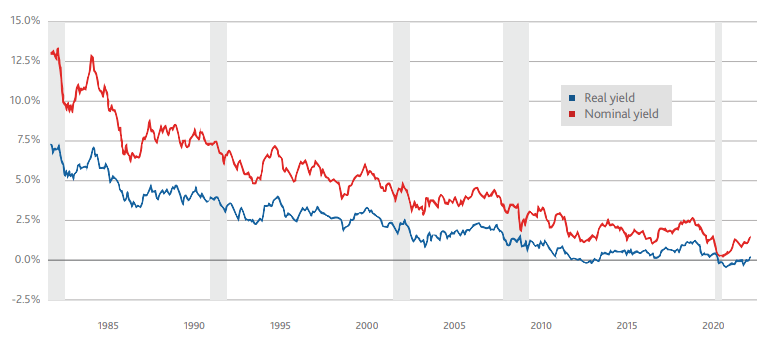

Both nominal and real interest rates have declined significantly over the past 40 years, a trend that has been further intensified by the monetary policy responses to the Global Financial Crisis and COVID-19.

Persistent low interest rates can profoundly affect retirement security by eroding investment returns and thus limiting the capacity of governments and the private sector to fund pension plans and other retirement savings mechanisms. As past retirement plan and saving decisions were generally based on expected asset returns higher than currently available, savers may not have accumulated enough funds to support planned retirement spending.

10-year nominal and real U.S. Treasury yields

The main sources of retirement income vary greatly across countries and, within countries, between income groups. In the U.S., for example, Social Security accounts for over 80% of the total income of elderly individuals with below-median income, while income from pensions and assets accounts for less than 10% (see 15 Most Effective Types of Investments for long-term).

For elderly individuals with above-median income, however, employer-funded pension income and income from personal savings grows in importance, accounting for about 20% and 10%, respectively, of total income.

Low-income households are less exposed to low interest rates, as their retirement income mainly derives from social insurance protection

In addition to macro-economic factors, the microeconomics of labour supply and demand are reshaping financial wellbeing. Structural economic shifts have contributed to work patterns which are characterised by less formality and predictability. Over the past decade, the number of gig economy platform workers has grown from virtually zero to 3% and 1.5% of U.S. and EU employment, respectively.

Technological drivers

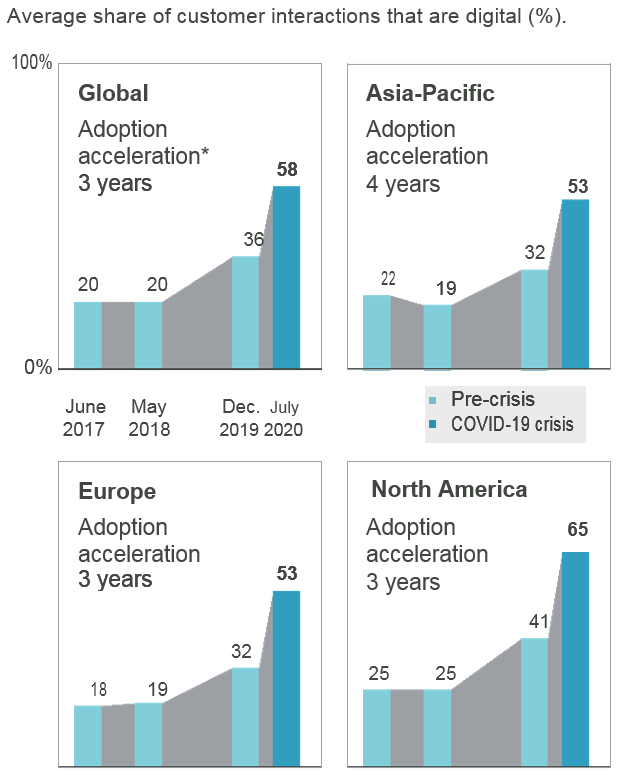

The pandemic has catalysed a digital transformation across multiple sectors at a pace not seen before. A recent survey conducted by McKinsey of senior executives showed that companies across the board have rapidly moved towards digital interfaces to interact with consumers and are now years ahead of where they were in the pre-pandemic era.

Rate of digital acceleration by region

Rather than being a one-off surge in the early stages of the pandemic, the trend has continued, with one recent survey showing that consumers continued to embrace digital channels in the six months prior to April 2021 at the same pace as at the start of the pandemic.

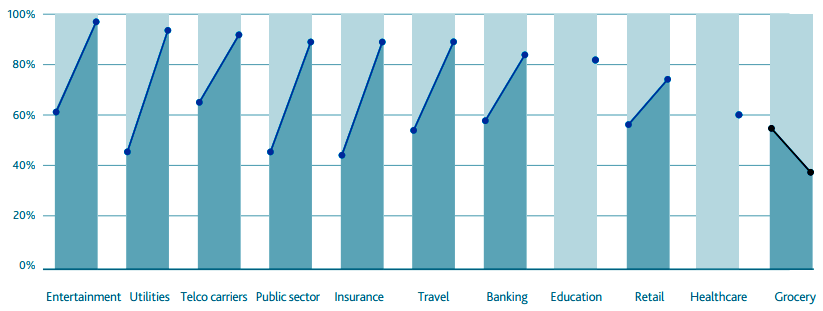

Consumer digital adoption in the U.S. and Europe by industry in the six months prior to April 2021

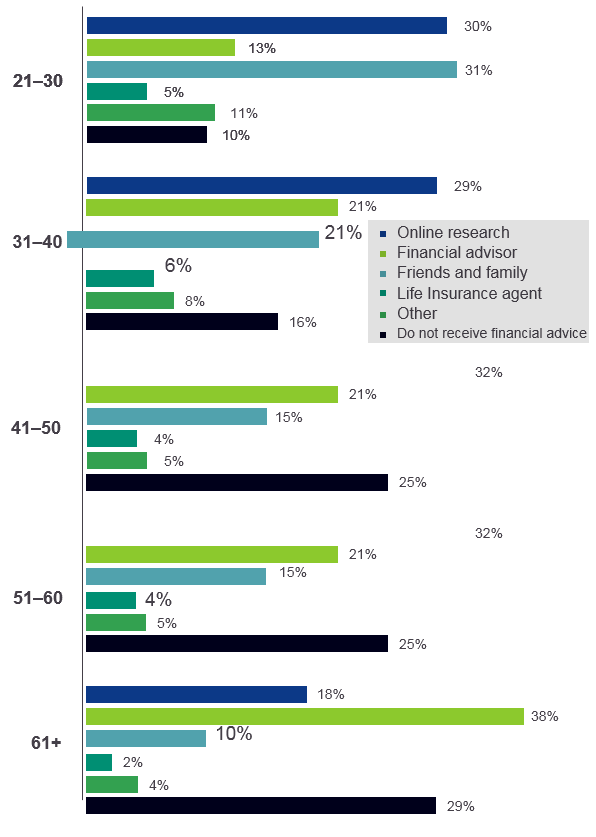

Demographics and technology adoption are intertwined.97 A 2021 survey in the U.S. conducted by Deloitte showed that almost a third of consumers aged between 21 and 60 years preferred using an online platform to initiate research on life insurance products, compared with less than a fifth of those aged 61 and over.

The pandemic has also had an inadvertent effect on consumer awareness of and interest in purchasing mortality protection among younger cohorts. A 2021 survey conducted by the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association (LIMRA) in the U.S. showed that 45% of Millennials expressed an interest in life insurance policies.

Applications among both Gen X and Millennials also surged throughout 2020. Encouragingly, U.S. life insurance companies with digital capacity and algorithm-driven underwriting have experienced 30–50% increases in sales since 2020. However, while some life insurers have made headway, the industry as a whole has been slow to capitalise on digital technology to advance its position.

Preferred financial advice channels by age

In order to make progress toward financial inclusion and narrowed protection gaps, technology needs to move beyond creating digital interfaces for marketing and distributing products to offering more attractive product pricing and customer experiences.

It is possible that the overall momentum towards digitalisation may fade as the world recovers from the pandemic. But it seems more likely that the awareness it has generated among younger cohorts, coupled with a maturing digital infrastructure, will have longer-lasting effects.

These technological tailwinds will likely create new market opportunities for life insurers as they cast their net wider to reach new (often younger) groups.

But digital engagement alone will not necessarily guarantee financial inclusion or appreciably narrow the protection gap (see Insurers` Digital Strategies for Personal Customer Engagement). For this to happen, the use of technology will need to move beyond creating digital interfaces for marketing and distributing products to offering more attractive product pricing and customer experiences.

Insurers will also need to do a better job of engaging the elderly, lower-income groups and small businesses, all of whom remain notably sidelined from the advances seen in digitalisation of financial services.

Four Recommendations for Insurers

1. Step up efforts to directly affect the determinants of savings and risk protection

Inherent in the concept of financial wellbeing is an ecosystem of consumer needs that transcends the traditional products offered by life insurers. If life insurers wish to position themselves more strategically, they will have to redefine their role to include directly affecting the determinants of retirement savings and risk protection through pathways such as education, advisory services, mentoring and financial incentives in partnership with government, financial advisors and wealth and asset managers. Doing so will require insurers to either create or buy new capabilities, or else partner to bring them in.

2. Promote financial literacy in young age

The lack of attention to financial education leaves the young ill-prepared to navigate the insecurities of the current labour market and successfully prepare for their eventual retirement. It also overlooks the opportunity to cement the role of life insurance at an early age. With a relatively modest investment, insurers can partner with national educational agencies, schools, communities and digital platforms to develop innovative ways of propagating financial knowledge, including by gamifying it, using social media and leveraging word of mouth and ‘influencers’.

3. Improve risk exposure through preventive measures.

Very few life insurers cited limiting risk exposure as a primary motivation for developing new financial wellbeing products. Yet there are strong connections between financial wellbeing, general wellbeing and risky behaviours. Altering these behaviours will require insurers to embed data science at the heart of their products and indeed to see it as a key to understanding needs, shifting the paradigm from repair/replace to predict/prevent. Similarly, using data science to better integrate health and wellness products could have significant benefits.

4. Tap into the longevity economy

Life insurers’ efforts to tap into the burgeoning longevity sector are currently modest. There is also little to suggest that their products address changing retirement patterns, such as unretirement, phased retirement and new careers post-retirement, or changing family structures, including shifts in multigenerational living arrangements.

New solutions such as silver sabbaticals to enable middle-aged adults to re-skill and to encourage longer working lives as well as supplementary health and care benefits that take over where government leaves off could help insurers unlock the potential of the silver economy and increase their relevance to ageing societies.

Concluding

Yet over the next few decades, the most fundamental trends shaping the future environment for retirement and financial wellbeing seem certain to continue, which makes improving long -term savings and protection ever more urgent. The challenge for life insurers will be to develop products that better meet the needs of increasingly sophisticated consumers while successfully navigating their own business future.

Financial literacy is at the very heart of financial wellbeing. Yet people continue to underestimate their future needs given increased life spans, as well as the importance of insurance in enhancing their financial wellbeing. Insurers have an opportunity to address this gap in the immediate term with relatively modest investments that focus especially on early age.

The survey findings make it clear that this is now sorely missing. There is evidence to suggest that early introduction to financial education can influence future financial behaviours and build financial confidence.

Insurers can play a prominent role by helping to develop national curricula, by working with schools, communities and third-party platforms, including digital platforms, and by mentoring students and their working-age parents.

Insurers can support financial literacy by helping to develop curricula in cooperation with schools, communities and third-party platforms, and by mentoring students and their working-age parents.

Much research demonstrates that there is a deep interdependency between financial wellbeing and general wellbeing, both of which may be highly amenable to preventive strategies to minimise risk exposure. These risks may include poor financial behaviours, such as inadequate savings, a too rapid pace of de-cumulation and erratic spending patterns, among others.

Broader wellbeing issues, including those that are health-related, may also have a knock-on effect on productivity, wealth accumulation, how and when people retire and their needs in old age. These risks can manifest themselves in different ways at different ages and levels of income and wealth, as well as vary by consumer preferences and attitudes.

Life insurers have an opportunity. Retirement savings and annuities could be targeted to support new needs of the ‘silver economy’.

Products could fund ‘silver sabbaticals’ that allow those over the age of 55 years to reskill and encourage them to remain engaged in the labour market. Products could supplement state-sponsored benefits, help pay mortgages or support dependents during work breaks, going beyond the standard income support insurance that is currently available.

Products could also support partial and phased retirement to offer the flexibility and work-life balance needed by older workers. The Swedish model of partial retirement may offer some insights regarding how voluntary life insurers might encourage employers to retain their workforce for longer.

…………………

AUTHORS: Adrita Bhattacharya-Craven – Director Health & Ageing The Geneva Association, Richard Jackson – President Global Aging Institute, Kai-Uwe Schanz – Deputy Managing Director and Head of Research & Foresight The Geneva Association