While there was sufficient capacity to meet the reinsurance needs of cedants at 1.1, it is also true that the amount of reinsurance capital being deployed was diminished. Cedants were, by and large, able to secure their required limit, but it came at a price.

According to Gallagher Re Natural Catastrophe Report, there was a clear desire from reinsurers to force change onto the market at the most recent renewals: pushing retentions up and restructuring programs to improve profitability for 2023 and beyond.

2023 became the fifth year since 2017 to cross the $100bn threshold. Total insured losses were estimated at $140bn, of which $125bn was covered by private insurers and $15bn by public insurance entities

- The reported combined ratio improved to 93.0% (HY 21: 94.1%), the lowest we have seen since 2015.

- The ex-natural catastrophe accident year loss ratio slipped slightly, from 59.8% in HY 21 to 60.2%, with rate increases not quite keeping up with inflation-driven rises in loss costs (see Insured Natural Catastrophe Losses). The expense ratio was slightly improved at 29.4% (HY 21: 29.6%).

- Although still below 100%, the underlying combined ratio deteriorated to 99.7% (HY 21: 98.4%), driven by an increase of 1.1 percentage points in the five-year average assumption we use for a normalised natural catastrophe load.

Macroeconomic Factors

Last year saw an unprecedented round of fiscal tightening in major economies, following more than a decade of low interest rates and cheap debt.

Reinsurers have historically deposited much of their investment capital into investment-grade fixed-income instruments to keep volatility out of their portfolios and maintain as much liquidity as possible in case cash is needed to pay claims.

This worked well during periods of loose monetary policy, as quantitative easing and other measures kept money markets stable. But in recent months, a supply chain shock led to widespread inflation, resulting in a ramping up of interest rates.

That in turn caused a significant drop in the valuation of investment-grade bonds (particularly at the short duration end of the curve where reinsurers tend to invest), leading to a decline in available capital on a market-to-market basis.

According to Natural Catastrophe Insight: Economic & Insured Losses, report demonstrated this, showing that for its cohort of global reinsurers, shareholders’ equity dropped by an average of 34% in the first nine months of the 2022, driven by threats of recession and the rise in interest rates, which resulted in lower market values of bonds and equities held by reinsurers.

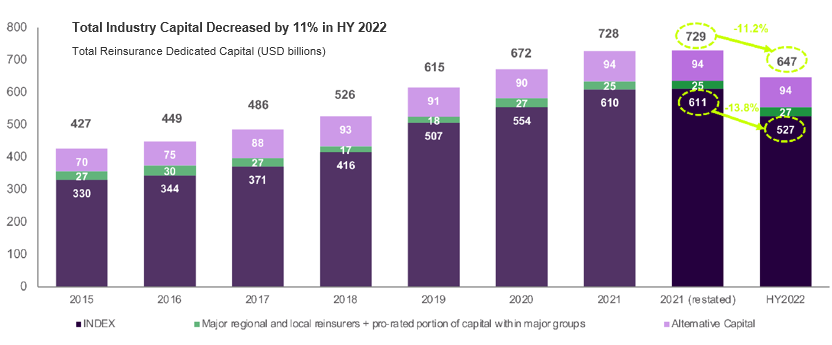

Total annual reinsurance capital

From a solvency perspective, many reinsurers were actually better off; rising risk-free rates resulted in higher solvency ratios as the reduction in liabilities—which in Europe are discounted at risk-free rates under Solvency II—exceeded the reduction in bond portfolio values.

However, the potential liquidity risk (that reinsurers may be forced to liquidate underperforming bonds, crystallizing the loss in bond value, to pay claims in the event of a large loss event) may be enough to make carriers think twice about whether they can afford to underwrite more natural catastrophe risk in the short term.

The underlying combined ratio was hit by increased natural catastrophe losses

| Subset | 2023 |

| Reported combined ratio | 93.0% |

| Remove prior year development | 1.6% |

| Accident year combined ratio | 94.7% |

| Strip out natural catastrophe loss | -5.0% |

| Strip out COVID loss | -0.1% |

| Ex-natural catastrophe accident | 89.6% |

| year CR | |

| Add in normalised natural | 10.1% |

| catastrophe loss | |

| Underlying combined ratio | 99.7% |

| Expense ratio | 29.4% |

| Ex-natural catastrophe accident | 60.2% |

| year loss ratio | |

| Ex-natural catastrophe accident | 89.6% |

| year CR |

Elsewhere as inflation increased, so did primary insured values, creating a need for greater levels of reinsurance coverage. But the financial uncertainty made it more challenging for traditional reinsurers to raise capital, along with the fact that higher interest rates made it more expensive to finance.

Hard Reinsurance Market & Hard Choices

According to 2023 Reinsurance Market Dynamics, while the primary and retro markets were the early winners in the burgeoning hard market, by the middle of 2022 those rate rises had also fed through to reinsurance premiums.

However, increased rates on their own were not enough to result in a wave of capital being deployed—appetites were impacted by a variety of factors, including but not limited to:

- How reliant the reinsurer is on retro to underwrite (and therefore the availability of retro, which for 1.1.23 was extremely late to show its hand, but did ultimately come to the party)

- A lack of third-party capital reloading given some capital remained trapped from previous losses (see Top Trends 2023 Global Reinsurance)

- Investors had a broader set of higher returning investment classes to consider in the rising rates environment, and many were concerned about existing modeling adequacy, and the impact of climate change on event frequency and severity

- A drop in the number of ILS players fronting elements of reinsurance coverage when compared with previous years

- A reduction in appetite for lower attaching retentions, given the impact of secondary perils on results in the past few years

- Increasing level of scepticism regarding whether reinsurers’ tools can adequately evaluate and price risk for the current risk environment, something that’s exacerbated by the implications of climate change

Much also depends on the state of the individual cedants. In the US, smaller or more regional clients clearing less than USD 200mn of capacity broadly found coverage, so long as pricing was set at an appropriate level.

Considerably more challenging were the larger placements, particularly USD 500mn and above, where the broadest level of participation across the reinsurance market was required to clear capacity.

For the larger clients, there was a continuation of what was seen in the 6.1 and 7.1 renewals in 2022; some programs were impacted by a modest number of reinsurers that held placements hostage with unrealistic demands for pricing and/or terms and conditions, but ultimately deals got done.

As an example, capital did come in for wind risks relatively late but, at high prices with low leverage, resulting in many cedants declining to take up offers. Cedants were not bullied into panic-buying at any price, preferring instead to take bigger retentions.

According to Global Reinsurance Market 2023, outside of the US, there was also no meaningful new capital raised for 1.1. While some underwriters moved out of the cat world altogether, choosing not to compete anymore after years of consolidated losses, others who were more highly geared were delayed in coming to market, initially left in the dark about their ultimate risk appetite until their retro providers showed their hand.

Those less reliant on retro were able to take advantage of this delay and grew their books accordingly.

Third-party investors historically play little part in the likes of European treaties other than through some fronting deals, given the more complex nature of the multi-peril coverage and multiples.

But there was even less capital deployed than normal here too, leading to a drain on capacity when compared with previous years, in particular around complex placements.

Concerns regarding climate change and the impact of secondary perils continued to grow among reinsurers too, particularly given the relatively light period for wind losses when compared with consecutive years of flooding and SCSs (see EMEA overview).

Any treaty with an element of loss frequency protection was difficult to place; lower layers were tough to find capacity for.

Aggregate excess of loss policies would now only attract capacity if they attached after three or four major losses, not after the first event.

And even where cedants might have been prepared to pay higher rates, there was a general feeling that reinsurers would do whatever was needed to give them the best chance of running a loss-free year in 2023.

This last point underlines a theme that resonated globally— property reinsurers, whether traditional or ILS, have largely failed to make money over the past five years.

The fact that losses have come from secondary perils, unmodeled perils, COVID, etc., is particularly challenging for ILS managers who have historically sold investors on being exposed to headline risk—the results have not borne that thesis out, which has also contributed to the lack of capital inflows.

The secondary perils experience has also led traditional reinsurance capital to largely move away from providing coverage at the lower levels, rejecting 1:3 year–1:5 year event coverage and instead coming in around the 1:10 level. It is a much simpler exercise to effectively underwrite yourself out of secondary perils by requiring higher attachment points (see Catastrophe Bond & ILS Market Review).

Reinsurance Solutions and Silver Linings

Despite the challenging conditions, renewals were largely completed—thanks to a combination of collaboration and innovation.

Cedants, that were able to, agreed to higher absolute retentions, and through their broker partners, some were also able to place meaningful absolute annual aggregate deductibles (AADs) on first layers in an attempt to maintain some level of earnings coverage.

In the US, clients also investigated the use of captives—particularly the idea of using a captive to sell ultimate net loss coverage to a company, and then employing a parametric hedge like an ILW/ bond/etc. to protect the captive and group results.

Brokers also helped establish innovation in structures, such as the use of non-indemnity solutions, which use a third-party vendor’s model of loss cover to run a footprint over a client’s portfolio post-event and, whatever that loss result is, that gets applied to the reinsurance layer, creating more certainty around loss outcome.

Looking ahead, there is consensus that more capital will flow into the market in 2023 and beyond. Even in the dying embers of 2022, companies were able to bring new capital to the property reinsurance market, and others were able to successfully complete equity raises.

Gallagher Re estimates that somewhere in the region of USD 1.5bn in new capacity was raised ahead of 1.1 for that renewal, although little of it was ultimately deployed, meaning there is some dry powder for the next round of negotiations.

Events such as the Floridian reforms announced at the end of 2022 will encourage more capital to play, most likely with those cedants considered best-in-class initially, as carriers dip their toes back in the water.

Ultimately, the industry has already proved that it is not a broken system, that even in the trickiest renewal many have seen in decades, deals got done; and that the market looks set to trade on into 2023.

………………….

AUTHORS: Steve Bowen – Chief Science Officer Gallagher Re, Tina Thomson – Head of International Catastrophe Analytics, Gallagher Re

Fact checked by Oleg Parashchak