Insurance-Linked Securities (ILS) have played a key role in allowing catastrophe risk to be transferred from the commercial insurance market to investors, providing much needed additional (re)insurance capacity. There has been talk for years about the potential of cyber ILS to transform the cyber insurance market.

According to Lockton Re’s Cyber ILS Report, the conditions of the market today are at a point where this potential can be fulfilled. Working with Cybercube Analytics and Envelop Risk, Lockton Re have created a market wide perspective on this topic.

Catastrophe risk driving innovation

In August 1992, Hurricane Andrew devastated many parts of Florida and the southern United States. It became notorious for the terrible property destruction and loss of life. But the far-reaching consequences for the reinsurance industry lasted long after the rebuilding was complete.

It became an inflection point for (re)insurers and regulators – more than a dozen insurers were declared insolvent due to the scale of the losses, with insured claims of over US$53 billion in today’s dollars.

There was a critical development because of the storm: the emergence of the ILS market. This enabled insurance risk to be transferred to investors in the form of a tradeable security.

ILS focused on providing (re)insurance capacity for extreme natural catastrophe events and trading in niche areas of property catastrophe (re)insurance until another dramatic milestone: the significant cumulative losses caused by hurricanes Katrina, Wilma, and Rita in 2005. Insured losses alone were over US$98.5 billion in today’s dollars (see Global Insurance-Linked Securities Market Outlook).

Capital markets were able to address the subsequent capacity shortage and provided a critical injection of over US$8 billion of catastrophe bonds in 2007.

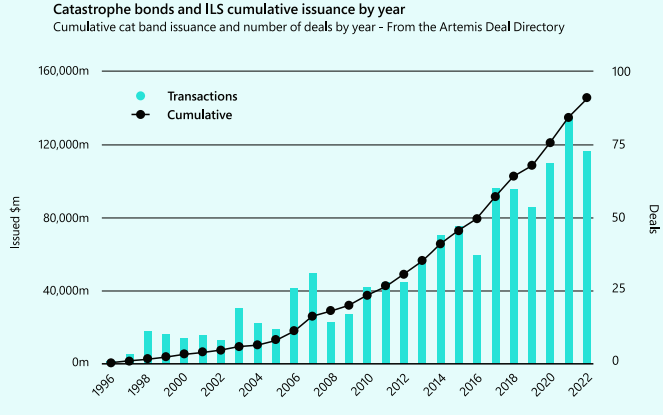

Since then, as illustrated in Figure 1 the ILS market has grown exponentially and with a cumulative cat bond issuance of US$120 billion from 2007 to today.

The dramatic growth of the ILS market in the last 25 years

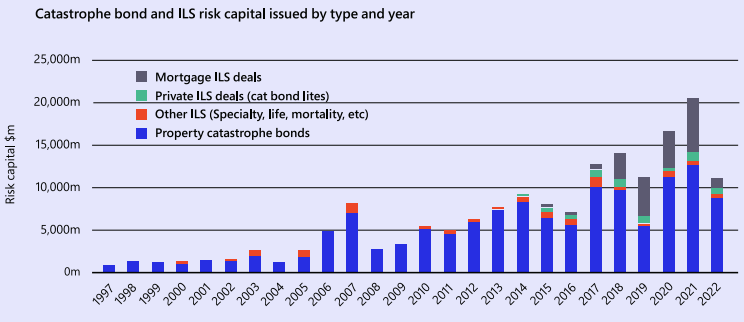

Perils covered in ILS transactions have evolved significantly from the peak natural catastrophes of hurricane and earthquake to broader natural perils including wildfire, winter storm, severe thunderstorms, and flood as well as non-natural perils including mortgages, mortality, and longevity (see about ILS & Cat Bonds).

The potential for cyber risk to be used as the basis for ILS investments was identified as early as 2015 in the insurance trade press, and the unfulfilled potential has been the topic of much debate since then. In this paper, the case is

made that the time and the market is right for ILS investors to enter cyber insurance in a meaningful way. One by one, the issues which have held back the material development of the cyber ILS market are being addressed. As the cyber insurance market has matured, so the concerns of both (re) insurers and investors recede.

The range of perils for the ILS investors has increased materially in the last few

Straining at the Leash

The cyber insurance market has evolved significantly in the last few years. The understanding of the fast-changing nature of the peril has increased and there is much more dedicated cyber security expertise now embedded within the insurance industry.

Cyber insurance is considered a core specialty insurance line by many enterprises, and no longer a luxury purchase, with demand continuing to increase.

This has enabled a more sophisticated assessment of the threats, more effective communication with technical buyers, and an ability to provide growing level of comfort within senior management at carriers.

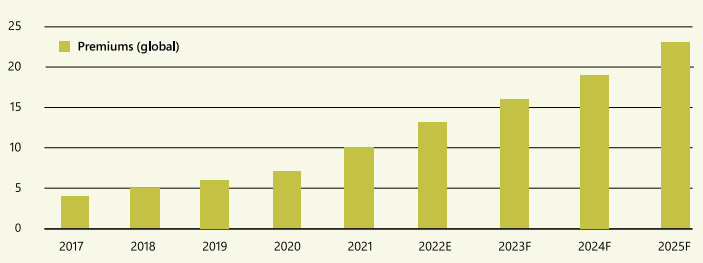

The dramatic growth of the cyber insurance market is expected to continue for years to come

Source: Swiss Re Institute

This growth is expected to continue for years to come. The multi-faceted risk landscape is better understood, as is the role insurance plays, alongside technical and procedural controls to protect companies and build resilience against a myriad of risks, ranging from rogue employees, criminal hackers, and politically-motivated activists.

Rates have increased in response to rising claims, so the value of the insurance has been demonstrated over many years.

Entire new segments are beginning to show promise such as cyber products for personal lines. Longer-term, some other lines of business may be (partially) subsumed into cyber – for example auto insurance will need to consider the cyber threat to autonomous driving systems.

Additionally, there are vast greenfield opportunities for potential buyers in new territories as well. The continued growth of the market must overcome concerns in two areas for its continued expansion.

Firstly, attracting additional financial capacity to support the solvency requirements as premium grows; and secondly, building confidence around the potential downside, especially as it relates to systemic risk.

These issues are interconnected and by addressing these challenges, the massive untapped potential of the market can be unleashed.

There remains a huge “insurance protection gap” between the current levels of cyber insurance purchased, and the total estimated economic consequences of cyber-attacks. These cybercrime costs are on track to increase to over US$10 trillion by 2025.

Consensus on trigger type

Early natural catastrophe ILS transactions utilising parametric triggers had the benefit of clarity in their purpose and scope. If a named storm hit a specific geographic area at a certain speed, a pay-out was made.

There has been much debate in cyber insurance circles around how to define an analogous event which is a discretely identified insured peril and can be measured appropriately.

One challenge has been the mismatch in expectations between potential protection buyers (sponsors) seeking all-peril cyber coverage ILS structures on one side, and investors on the other side more interested in transactions which have only very specific, clearly defined cyber perils included.

The peril being covered needs a common understanding of its nature and the event definition is key.

Interconnected technology operates without interruption in a borderless world. In this scenario, unlike specified named perils, in theory all cyber risk could cascade across all companies around the world. The reality is different.

Although there clearly are some elements of connectivity between regions, there is significant segmentation built into the large global internet infrastructure providers.

Additionally, there are inherent cultural variations and adaptations in how companies build and rely on different key technologies, so there is a complex patchwork of different technologies across industries and geographies, leading to a much lower risk of a single vulnerability spreading globally.

One way to limit this risk within the ILS context is to impose geographic conditions on a transaction. Depending on the portfolio, this could be a valuable way to address these concerns.

In the world of property cat reinsurance, trigger types are often broken down into three main categories: ultimate net loss (UNL), parametric and insured industry-loss (index). All three are traded as part of excess of loss reinsurance structures, with ILS investors able to assume this risk via various means.

Some reinsurance companies offer specialist fronting services, which can provide valuable non-recourse leverage to the end consumers of risk. Other third parties specialise in the provision of licensed transformer vehicles able to write reinsurance and package it into securities.

The risk transfer mechanisms, and the associated market infrastructure can be harnessed and used for cyber ILS, though certain nuances of cyber are acknowledged.

The selection of trigger type will vary based on the particulars of a transaction, but there is an emerging consensus that each of these can serve the needs of the cyber insurance market in different contexts.

The concept of parametric triggers translates naturally from property cat into the world of cyber reinsurance. The mechanics and rationale are unaltered: the need for an independent, competent calculation agent to determine whether a defined parametric threshold has been triggered.

This determination is made post-event, giving both the protection buyer and ILS investor certainty as to the quantum of pay-out. The short-tailed nature of the product is what makes it appealing to investors, with no residual uncertainty or protracted settlement process.

A trigger that responds to a defined period of cloud outage at a specific service provider would be an example of a cyber parametric trigger.

Industry loss indices for cyber catastrophe events have been available since 2017 and appeal to some ILS investors, many of whom already understand the concept from industry loss warranty (ILW) products traded frequently in the property catastrophe market.

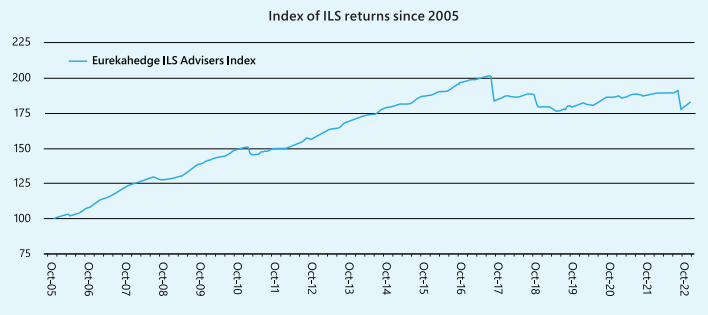

ILS returns have stalled in the last few years due to increased natural catastrophes

The loss development tail over time for cyber events in the collateral release mechanisms of these contracts, is an issue to address upfront. The goal is to strike a balance between buyers’ need for protection and sellers’ need to free up collateral after an appropriate length of time post-event.

UNL is perhaps the most challenging for cyber ILS instruments. The buyers’ attraction to this trigger type is self-evident: risk transfer with high confidence that the pay-out will match actual losses incurred is preferred. ILS investors, however, may be circumspect for a few reasons.

Firstly, for the uninitiated, there can be a misconception that cyber coverage is ill-defined or amorphous. The reality is very different, however. Cyber insurance policy forms have matured over time with a convergence of standardised heads of cover offered in most products.

With twenty years of loss experience behind it, the industry has clarified intent and evolved coverage over time. Key exclusions are also becoming more standardised, particularly for systemic events like war, critical infrastructure failure and state-on-state cyber operations.

Secondly, some ILS investors may be dissuaded by the longer loss development tail of third-party liability (TPL) claims.

While TPL losses can take longer to fully develop than first-party losses, historical large cyber events have typically exhausted their cyber insurance programmes quickly due to sizeable first-party elements of the loss; third-party elements were therefore limited components of the overall loss quantum.

Cyber insurance is typically written on a claims-made basis which naturally reduces the development tail for all losses, both first and third party.

With certain limitations, negotiated collateral release mechanisms can enable capital to be freed up efficiently.

Ultimately, the extent to which the ILS community embraces each of the three trigger types will depend on several factors. Education about cyber risk and the underlying coverages is key for new investors, and due diligence will take time.

Price is obviously paramount: protection buyers will expect a discount over UNL pricing in return for accepting the basis risk associated with parametric and index products, which might fall short of sellers’ expectations, even in a hard reinsurance market.

The cyber insurance market is set to continue growing and the insurance market penetration is increasing in established and emerging markets alike. There are limits to traditional market capacity to take on this extra demand and each of these cyber ILS triggers have a role to play.

Systemic risk understanding

The 2017 NotPetya attack is the closest there has been to a cyber catastrophe. Economic losses were approximately US$12.5 billion (in 2022 US$) arising from the devastating malware, which deleted data and crashed systems among multiple global companies, including Maersk, Mondelez and Fedex.

Most of the losses were either uninsured, or not covered by dedicated cyber insurance policies.

This demonstrated the potential for catastrophic losses and focused the minds of cyber exposure management and modelling teams across the insurance industry (see New Cyber Risk & Ransomware Trends).

Investors are most open to potential investments where the realistic disaster scenarios (RDS) have three specific characteristics: firstly, scenarios which can be as clearly defined as possible at the point of transaction; secondly those which can be ring-fenced post event; and finally, those which have a rapid resolution from a claims settlement perspective.

There is growing convergence within the cyber insurance community, with support from regulators on the type of events which are most likely to impact the industry in terms of frequency and severity of cyber-related losses.

Three categories of catastrophe event are most common in how they are assessed by regulators and portfolio risk managers:

- widespread data breach at a critical technology provider, such as an electronic payments service

- malware attack (which could include ransomware) on a key supply chain software provider

- cloud services outage (disabling access to critical services by users)

These scenarios, though necessarily reductive in nature, distil an infinite set of permutations of potential threat actors, threat vectors and outcomes into a digestible format which can be analysed and compared both between scenarios and over time.

The intent is to create relative benchmarks for comparison between portfolios, as well as create a common lexicon and understanding of the risks between counter parties.

One major source for improving the understanding of systemic risk has been the investment and development in cyber catastrophe models, which have now been scrutinised over several years and are growing in acceptance.

ILS Model maturity

Some ILS investors have had the view that cyber (re) insurance losses are intrinsically un-modellable and that cyber underwriters lack the means to adequately quantify the risk. In addition to data collected by (re)insurers, there has been undeniable progress in the methodology and data which support cyber risk catastrophe models.

Initial models were somewhat simplistic and deterministic, based on top-down aggregated market share data regarding the scope of a potential event.

Cyber modelling has evolved in how it defines cyber events, creating clear differences between cyber perils, and adjusting modelling methodologies accordingly.

In recent years, improved scanning technology and data capture has helped build credible datasets that identify dependencies between companies and the technologies they rely on. Models are now able to display statistical analysis based on actuarial probabilistic techniques to show a range of potential outcomes, effectively illustrating insured exposures.

A more focused scenario set has developed, based on market demand, which reflects the key priorities of cyber (re)insurers. They have also evolved to reflect new insurance products more closely and the specific types of costs which are covered.

A structured approach to analysing the potential frequency, footprint, scope of impact and severity provides a repeatable and scalable model for the market and ILS investors.

There has been a big effort to educate potential investors, who typically are not specialists when it comes to cyber risks. Building confidence and credibility in the models being used is a keystone to the acceptance by investors in the thresholds at which exposure attaches, and associated pricing.

The conversations are framed in the vocabulary of traditional catastrophe management, and a lot of progress is being made. There is now a growing critical mass of investors who are looking for new ways to benefit from different types of catastrophe risk securitisation.

Ongoing investment in cyber catastrophe models continues and the update development cycle is shortening.

One area of focus over the next couple of years is moving from a range of individual cyber catastrophe events to umbrella categories of cyber catastrophe event types, which captures a broader set of groupings.

Turning data into insight

Back in 2006, the phrase “data is the new oil” was first attributed to British mathematician Clive Humby. More than 15 years later, this analogy has broadly held up, as unless its potential is harnessed through refinement and product innovation, the raw material of data has limited value in its unrefined state.

ILS investors raise concerns that there is insufficient data to calibrate cyber loss models.

Yet policies today provide cover across all industry verticals to a diverse range of insureds on every continent, and over 20 years’ worth of exposure and loss data exists with which (re)insurers can inform their view on cyber risk. In the initial stages of the market, insurers partnered with the reinsurers, using quota share reinsurance to transfer and share risk.

With a direct look-through to each underlying claim and policy subject to the quota share contracts, first movers in cyber treaty reinsurance were able to build comprehensive data spanning much of the market.

Cyber risk is inherently data-driven and many aspects of it have a digital footprint.

The best operators in the space have built mature analytical capabilities powered by this data, with machine learning, data science and statistical methods able to quantify loss potential.

Another concern often raised by ILS investors is that, even with extensive data sets, it is impossible to quantify cyber risk to any degree of precision due to its dynamic and ever-changing threat landscape.

There are inherent challenges in assessing catastrophic cyber threats, in that the tools, techniques, and procedures of the threat actors change frequently. It is a constant tug of war between attackers and defenders of networks.

As a result, historic loss data is less valuable to (re)insurers assessing the frequency and severity of risks compared with more stable perils. It is true that this state of flux is one of the biggest differences between property catastrophe risk and cyber.

While earthquake and hurricane risk remain relatively steady over time, cyber risk appears chaotic and unpredictable.

There is no shortage of cyber security data sources available, such as network scanning, supply chain tracking, and end point detection and response software.

The challenge is leveraging the right combination of data to turn it into insight, so that better decisions around capital deployment can be made. Building an ecosystem of data providers across different categories provides a substantial lift on the accuracy and precision of the outputs.

…………….

AUTHORS: Oliver Brew – Lockton Re Cyber Practice Leader, Zach Breslin – Lockton Re Capital Markets Leader, David Ross – Envelop Risk Executive Vice President of ILS & Capital, Brittany Baker – CyberCube Vice President of Solution Consulting, Yvette Essen – CyberCube Analytics Head of Content, Communications and Creative

Fact checked by Oleg Parashchak